|

Shiramine

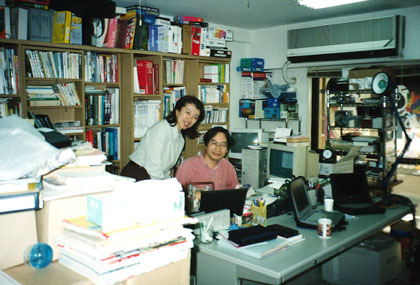

The air is crisp and cold, and the view from the Shiramine chairlift is pleasant. I follow Kiyoharu as he pushes off from the chair and slides down the ramp, stopping at the top of a steep and bumpy chute of snow. We look down over a valley, where a small town, perhaps looking shabby in the summer months but now quiet and clean under a fresh layer of snow, sits alongside a small river. We arrived here via a four-hour drive from the city, two families plus me packed into a Toyota Hi-Lux minivan with piles of gear and skis strapped to the rack on top. All of us are checked into two large rooms at the ryokan (traditional Japanese Inn) located at the base of the ski slopes. It had not been my plan to come along (I had stopped to visit for just one night, en-route to Yokohama), but the invitation was too hard to resist. I agreed to come along, thinking only that I might spend time at the ryokan catching up on some work with my laptop and perhaps studying Japanese. But one temptation led to another and now here I am, watching my breath make steam in the early afternoon on the top of a small mountain. Kiyoharu looks dazzling in his bright red and silver outfit with color-coordinated hat, gloves, boots and brand-new Rossignol skis. We adjust goggles and straps, and he points down the chute. "Good run," he says, "Okay?" Not wanting to look timid, I nod my approval, although the slope becomes more pronounced halfway down and I have no idea what might lie below. He gestures again down the slope. "Dozo", he says. This is to be my first run of the year, in rented boots one size too small, on skis of unknown vintage, wearing borrowed clothing (very stylish, by the way: gold with lavender trim, women's size XXL, the only thing the rental shop had that approximated my size), and he wants me to go first. I don't think so. "Ie, dozo," I insist, waving a glove. Kiyoharu launches himself straight down the slope, carving perfect turns between the bumps. He's more than just show in his hundred thousand yen outfit; it's obvious right away that he's a much better skier than I am. But I'm afraid that I might misread a sign and fly off a cliff if I lose him, so I grit my teeth and shove off without delay, following Kiyoharu down. Holy Teflon! I don't know what that stuff was that the guy at the rental shop was wiping on these skis just before passing them over the counter, but they are fast -- too fast. Within seconds I seem to have hit terminal velocity. I have very little control, my toes are pinched and screaming, and it just keeps getting steeper. After bashing over a dozen moguls I nearly fall, wrenching my thumb trying to catch myself but losing not a bit of forward momentum. Kiyoharu is visible ahead, looking like an ad for Sapporo Ice Draft as he cuts left and right, pure style with plenty of speed. Meanwhile I'm just bombing right over the bumps, arms akimbo, knees slamming chest, rump slamming snow -- just flesh, bone and plastic under the relentless influence of gravity. Somehow we get down to the flats and Kiyoharu slides in a shower of powder to a perfectly carved stop. He raises his goggles and turns left to look for me just as I slither behind him on the right, unseen. I come to a sloppy finish, pointed nearly uphill with my ski tips forming an imperfect V, and stand there panting. Kiyoharu shades his eyes and looks for me, then finally glances back down the hill and sees me below him. He leans back, surprised. "Honto! Expaato skier desho!" he yells. I rub my battered thumb and try to catch my breath, and consider lunch. Nozomi Express Traveler's tip: do not assume, as I did, that the sleek white Shinkansen (bullet train) that you see parked on the tracks, at the platform location printed on your ticket, is the train you are supposed to board. In fact, if it is more than ten minutes before departure time you can pretty well assume that it is not your train. I had a reserved ticket on a Hikari Express departing Shin Osaka station at 4:05. I arrived at the station with time to spare, stopped and checked email at a phone booth (more on that later) and poked around the station a bit before going to my appointed track. It was ten minutes to 4:00, and there was a train parked at the platform. I boarded the train, put my bag and coat on the rack above my seat, and then stepped outside to get a can of orange juice from the nearby "Let's Kiosk". As I paid for my juice I heard the familiar jingle that tells you "the doors are about to close". Surprised, I hopped back on the train just in time to avoid losing my clothes and computer. I looked at my watch, then at the clock on the platform. The train was leaving the station six minutes early. Trains in Japan never, never leave early, and only rarely are they even one minute late. Could this be the wrong train? The answer to this small riddle came in the form of a friendly recorded voice (in Japanese and English) telling me (and seemingly only me, as I was the only person in the car) that the train was a "Nozomi Express" bound for Tokyo, with one brief stop in Nagoya. That would have been all well and good, but I was only going as far as Yokohama, where the train would not stop, nor presumably even slow down. What to do? The conductor finally came through to check tickets, and he seemed to understand right away what had happened. "Nagoya," he said, "change train". No problem, I thought to myself. Even if I need to reserve a new seat, my JR rail pass means it won't cost a single dime -- er, I mean Yen. After a short time we reached the city of Nagoya. I was ready with my bags, expecting that my real train would be five or six minutes behind this one. There was no time to talk to a ticket agent, so I gambled that my old ticket would still be valid, even though the conductor in the first train had already put his stamp on it. The train stopped and I hopped out onto the platform. Surprisingly, right on the other side of the platform was another train, this one absolutely, positively displaying "Yokohama" on its reader board. Before I could investigate further I heard that familiar tune again, so I jumped aboard the new train and found my assigned seat. Again the train was nearly empty as I settled in for a smooth ride north. But what was this? Why was the conductor on this train looking at my ticket and shaking his head? And why was he gesturing for me to get out of my seat and follow him? I started feeling the unfocused dread of knowing that I was on the wrong side of the rules. I walked past the few other passengers in the other cars, feeling like a soon-to-be-convicted felon. We walked about five car lengths back on the train to find a tiny office. The first official, who I shall call Conductor Number 1, handed me off to Conductor Number 2, an attractive but befuddled-looking young woman. From their interaction I judged her to be the senior conductor -- at least for the moment. Conductor Number 2 looked at the ticket, scratched her head, then looked then at me quizzically. I could almost see the questions hanging over her head, in cartoon balloons: How did I get on this train with this ticket? Who stamped it? What kind of a scam is this? I tried to be helpful, but my explanations didn't seem to register. I pointed to my watch, then to the ticket. "Yon-ji go-fun desu". I began, "demo, mistake… san-ji gojyukyu-fun..." No response, just a blank stare. I lapsed into broken English: "Nagoya, change train?" It still wasn't working. Conductor Number 2 shook her head in confusion, then picked up a phone handset and began speaking to someone on the other end. Conductor Number 1 was busy typing information into his hand-held fare calculator. He pressed a final key with a flourish and a strip of paper rolled out, printed with a figure: 9400 yen, nearly one hundred dollars. "Wakarimasen," I protested. I handed over my rail pass, "JR rail pass desu, ne?" Conductor Number 1 waved away the rail pass. Conductor Number 2 thought for a moment, then assembled a bit of English to help explain. "I want more money," she said slowly. Again I tried offering the train pass, my dog-eared talisman. Conductor Number 1 was flipping through a binder. He produced a worn-looking scrap of paper. On it was printed a single message in large, easy to read type: "The JR rail pass is valid for all JR trains, buses, and ferries with the exception of Nozomi Express." I suddenly remembered the sign above the train, back at the Nagoya platform. Next to "Yokohama" was the bright green word: "Nozomi". This was not my train, Yokohama- bound or not. Conductor Number 2 was on the phone again. Soon another conductor arrived, this one older and possessing a look of real authority. This conductor, Conductor Number 3, quickly sized up the situation. I could see immediately that I had been judged and found wanting. I started thinking I should dress better when traveling, and shine my shoes as Sensee suggested (even if they are mostly canvas). Conductor Number 3 looked at the fresh scrap of paper held by Conductor Number 1. He shook his head. He looked at my old ticket, and pointed with his finger at the printed departure point of Osaka. He said saying something about Nagoya, and "Nozomi". Conductor Number 1 nodded and put the scrap into his pocket. "Chotto mate" (just a moment), he said, then again fiddled with the fare calculator. Out came another scrap. On this one was printed a new figure: 13500 yen! "Wakarimasen," I stammered, "mistake, ne?" Conductor Number 2 had her phrase book out, learning more English: "You must purchase ticket," she said. "Again purchase." Now I understood: they were charging me not only for Nagoya-Yokohama (at the exorbitant Nozomi fare), but for the Osaka-Nagoya jaunt as well, which was also a Nozomi. I looked at them with pained disbelief. There was a long moment of silence. Finally Conductor Number 3 half smiled. He spoke English, "It was mistake?" I nodded with whatever humility I could muster. He looked at the others with an air of certain power, making it clear that only he had the necessary authority. He's enjoying this a bit too much, I thought to myself, but appreciated the inevitable result. He waved me away and I skulked back to my seat. I arrived in Yokohama well ahead of schedule. The Post-bubble Era I'm walking with Katsumi through the central Kannai ("inside the gate") district of Yokohama City in mid-morning. This is the best time of day to walk, it seems. Schoolchildren and workers ("salarymen" and "office ladies") are all installed at their desks and off the streets, and the frantic activity of afternoon has not yet begun. In mid- morning, you can stop in a café for a pastry and coffee without enduring clouds of smoke from men in suits, and you can stop and talk with sales clerks without feeling rushed by the line of people behind you. Katsumi is talking about Japan's post-bubble society. "Too much self-criticism", he is saying. We go into a bookstore and he waves at the display racks by the door. "These shelves were, two years ago I think, just all books criticizing Japan. Japanese writers, always so negative, and public bought these books… it was a sort of self-abuse" He laughs a bit and picks up a book to examine. "Now it has changed a little bit", he says, waving the book in the air. "Now the popular books criticize Japanese self-criticism... so stupid!" Katsumi's office is actually a small apartment on the second floor of a mansion (high-rise apartment building) near the center of the city. Apparently the building has a mix of tenants, ranging from small families crowded into one- and two-room units to small businesses like Katsumi's that are wired to the world via high-speed ISDN lines, cell phones and fax machines. The office is small, measuring no more than twenty feet by twelve, but is packed to the ceiling with bookshelves, worktables and computers. Boxes and books, odd bits of computer hardware, software manuals… There is stuff piled in every available space, making it impossible to walk a straight-line course through the room. Katsumi's part-time technical assistant (a student from a nearby college) works at a computer behind a large monitor, mostly hidden from view. Yukiko, a part-time sales and marketing person working for Katsumi, arrives at the office at noon. She wears torn jeans, a Nike sweatshirt and comfortable-looking sneakers. She is not the stereotype Japanese "office lady", but perhaps represents instead the new Japan, said to be a better place for women with talent and a strong will. But for every Yukiko with her torn jeans and direct talk, there are a hundred others who run right into Japan's male-dominated corporate culture, and who find themselves making tea for meetings as the end result of their efforts to obtain a degree and land a good job. I haven't seen Yukiko in a year but my mind blanks and I can't remember the correct greeting. I remember she has a daughter and ask after her. "Home today," says Yukiko, "No school, big Japan influenza." Yukiko is an interesting woman – at 37, she is young enough to represent the new generation of Japanese woman, and old enough to have experienced the worst of Japan's cultural chauvinism, the "bubble" years of the 1980s, as an adult member of society. Yukiko is divorced, living with her 10-year old daughter in Tokyo. In this aspect she is not unique; Japan has a fast-increasing divorce rate. Whether this fact is just one result of the slow collapse of Japan's traditional culture or indeed a factor in that collapse is a matter of no small debate here. In any event, newly independent women are asserting a more visible public power in Japanese society. Even outside the metropolitan areas, women are reportedly becoming more active in grass-roots politics. Fed by sensational television and newspaper reports (democracy is alive and well on Japanese television), in 1990 there was a huge grass-roots campaign, primarily involving Japanese housewives, to oppose proposals in the Diet (the Japanese parliament) that would have modified the constitution and authorized Japan's direct military involvement in the Gulf War. There have been a series of such events in the post-1990 era that have helped to push Japanese women into activism and a more visible role in society and politics: the 1995 Kobe earthquake, the Aum Shinrikyu subway attacks, the domino-like fall of one prime- minister after another due to corruption scandals, the loss of a generation of husbands to overwork and stress. With more and more highly educated, freshly motivated Japanese women observing these events via the Japanese mass media, and with more of these women exchanging information and opinions via the Web, can Japan expect anything less than a social revolution? In 1997 the government's bungled response to a major oil spill on the Japan Sea Coast became yet another rallying point for activists – both male and female. To many progressive Japanese, the government is seen as a huge, bumbling caricature of the Japanese salaryman, out of touch with life outside and unable to react with creativity or compassion in the face of crisis. This is probably a grossly unfair characterization, but during the Japan Sea oil spill the enduring images were of Japanese citizen volunteers (mostly women) scrubbing crude oil from rocks using inadequate gloves and safety equipment (five volunteers died of heart attacks during the hastily-organized efforts to contain the spill, which dwarfed the Exxon Valdez disaster) while government bureaucrats debated whether there was really a problem requiring a response. (More recently, the long-simmering frustration over women's lack of access to birth control pills -- still outlawed in Japan after nearly thirty years of safe use elsewhere -- brought the reality of women's political power into direct public focus. When the male importance drug Viagra sailed through the approval process in an astoundingly short six months, the resulting political backlash surprised and humiliated the government into finally fast-tracking the Pill.) Katsumi, Yukiko and I meet Katsumi's wife, Tomoko, for lunch. We have tonkatsu (fried pork filet) at "one of the oldest tonkatsu places in Japan" according to Katsumi. The building housing the restaurant looks much like all the other functional but ugly aluminum and stucco structures in the area. I ask Katsumi how recently most buildings here were constructed. Of course, he says, most were built after the war. Virtually all of Tokyo and Yokohama were destroyed by fire-bombing. Home Sweet Capsule I leave Katsumi's office at 3:30 in the afternoon. I have nearly a week of free time, my train pass, a bag of clothes and a computer. I have no firm plans other than to explore the country in winter. I leave Yokohama via train, traveling from Kannai station to Ueno in Tokyo. At Ueno, I reserve tickets for the following morning, departing Tokyo station to Hakodate (in Hokkaido) via the city of Morioka. My plan upon leaving Yokohama had been to take a night train to the city of Sapporo, but after arriving at Ueno I make the last-minute decision to spend one night in Tokyo. After I have the tickets I get back on the train and ride two stations south to Akihabara, also known as "electric town". Akihabara is nerd heaven; visualize the sound and lights of Las Vegas overlaying hundreds, perhaps thousands, of large and small stores selling everything from computers, televisions and other home and business products to street vendors peddling the smallest of electronic components, which are laid out like vegetables at a market. (There are persistent rumors that infiltrators obtain much of North Korea's missile guidance and other advanced technologies by shopping at Akihabara.) I notice that the advertised prices are down substantially, and are now competitive with prices in the states. This is a big change, and one that Katsumi will later attribute to the Web. It is becoming impossible for Japanese companies to gouge their customers for goods that can now be purchased quickly and easily -- and with now-popular credit cards -- via the Web. The result of this is a leveling of prices worldwide. It really is impossible to overstate the importance of the Web (and lower-cost methods of communication, including the now ubiquitous mobile phones carried by seemingly everyone above the age three) in changing the traditionally hierarchical systems of Japanese society: the quick exchange of information for grass-roots activism and the democratization of commerce are just two aspects of this change. And of course my ability to continue working while on this trip, with essentially no impact to my customers, is another aspect with immediate benefit for me. While in Akihabara I step into a phone booth, prop my laptop on the metal tray that fronts the telephone, slip in a phone card and check my email -- something I am still unable to do reliably in the United States. While in Japan I'll perform this routine as many six times a day, using local MSN dial-up numbers to access my usual (non-MSN) email account from phone booths that are always located just a few steps away, in any city. No one needs to know that I'm answering their messages while standing in a noisy phone booth that is plastered on the inside with soft- core pornographic advertisements for "escorts" and "120 percent service" massages, on the side of a busy street in Asia, halfway around the world. (More than one customer will comment on my unusual working hours, however…) Then I'm back on the train and on to Tokyo station, where I decide to call Yukiko, who lives with her daughter near the city center. I ask them to dinner. They are already eating but Yukiko says they will come anyway. We have a fun evening; I trade Japanese and English lessons with Yukiko's daughter; she (ten years old) asks why America-jin have such big noses and big eyes. She asks other things, like why is the diagonal of a square longer than its sides. I don't really have acceptable answers. After they leave for their apartment I try to find a cheap hotel, with no luck. I have a low- level curiosity about "capsule hotels", and make some effort to find one near the station. Two helpful women at a pharmacy give me advice. They are restocking a vending machine while they talk; another woman walks up while we are conferring and offers the opinion that the Tokyo station area does not have any capsule hotels. Finally they suggest I try Ueno station, where I had bought my tickets earlier in the evening. Knowing that my Shinkansen will stop at Ueno after leaving Tokyo Station, I go to a JR office, change my ticket to depart Ueno rather than Tokyo, then get back on the local train and head up to Ueno. I spot a sign for a "kapuseru hoteru" right outside the station exit, summon up a small bit of courage, and walk right in. The hotel I've picked is up a narrow staircase with worn red carpeting and lounge music playing through bad speakers in the wall. At the top of the stairs things get a little strange. Everything is cramped: the ceiling is low, the furniture (such as it is) is low and very old looking, and there is a step up to a raised floor that cuts into the already diminished headroom. The overwhelming theme is dark red velvet. There is a nude quasi-Greek statuette at the top of the stairs, and I wonder briefly if this establishment is really what it claims to be. The man behind the counter seems quite surprised to see a foreigner. He had absolutely no English to offer, so our business is transacted mostly in sign language. The routine is a bit complex; this is not ryokan (Japanese traditional Inn), but there are certainly similarities. First you remove your shoes and put them in a locker. This requires one key. After putting your shoes in the locker you give the key back to the counter-person and get another key, this one attached to a wristband. You are then shown to your clothing locker. You change out of your clothes and into a yukata (cotton kimono), and can now proceed to your capsule, or to various other rooms in the hotel. (And apparently you can wander outside in your yukata as well, as evidenced on the street outside when I later stepped out myself -- more fully clothed -- for a beer at the pub next door.) The capsules themselves are stacked two-high (I have been given an upper one), and are curtained at one end. Inside there is a bad radio, a bad TV (with optional porno channels, judging from the sounds across the way), and a built-in alarm clock. The speakers for the radio and TV inexplicably face the curtained end of the capsule (the TV screen faces inward), resulting in the neighbor across the hall having a clear shot (hearing-wise) from your selected channel. The capsules are made of fiberglass and measure about three feet wide and three feet high -- just enough to sit up. Each capsule is about 6 feet long; it is not much different than sleeping in a small tent. Bathing facilities are common, and are set up like a public bath or onsen (waist-high showers you squat or sit in front of, and common baths). This particular capsule hotel also doubles as a sauna and massage studio (not that kind -- I can see from the advertisements that the masseuses are male). In this particular capsule hotel, you can actually find out all you need to know about the place by standing in the reception area and watching the security monitors behind the front desk. They randomly flash from one view to another, leaving no area unwatched, including the changing areas, massage rooms and showers. Katsumi tells me these places are eminently practical, and I can see why. If it takes a commuter two hours to get home on a crowded train (this is not unusual), and two hours to get back to work in the morning, then why bother to go home at all when the boss makes you work late? It costs about $30 to stay in a capsule hotel, and you have all the services you need. Pay a little extra and you can have a nice sauna and/or massage as part of the bargain. And because no women are allowed, your spouse can rest assured you are staying out of trouble. (Of course the larger business hotels around the corner have their "alibi channels", but that is another story for another time...) Seems great to me. If only the guy across the hall would turn off "Tammy Does Tokyo"... Hokkaido It is morning in my capsule. I've gotten very little sleep due to the snoring of my neighbors mixed with the non-stop groaning and panting from a nearby porn flick. I've slept three hours at the most and I leave without taking a shower, taking only the time needed to shave and splash some water on my face. At Ueno station I experience more confusion about whether I have the right train. The seat indicated on my ticket does not exist, and the train has left the station at 6:58, not 7:00. It doesn't sound like much, but this is Japan. The conductor seems unconcerned; it seems this train is in fact going to Morioka (where I must make a connection), although it might make additional stops along the way. I'm relieved that I challenged the Japan Rail agent the previous evening when I made the reservations. In a typical demonstration of JR's tight scheduling, he had given me only seven minutes between trains in Morioka. I had expressed my concern (in very stumbling Japanese) and asked for an earlier train to Morioka so I would have at least 30 minutes to find the correct platform. Now, arriving on a different train that may arrive a later time, I'm happy for the extra minutes and hope the train arrives not too much later than originally planned. (It is a near-certainty that it will not arrive earlier than my assigned train. The JR agents seem to delight in quickly finding -- often without the need to consult schedules -- the fastest route from one point to another.) It seems to be okay -- the conductor finally makes me understand that there is just one additional stop, where half of the train will split off and go to Akita, while this half will go on to Morioka. I find a free seat, relax and watch the scenery out the window. The snow is about six inches deep out there, and it looks very cold. There are many more trees here than in the Tokyo area, and the morning air is noticeably cleaner. It's astonishing to think how concentrated the population is in the Tokyo to Osaka corridor, given the number of train lines that lace the remainder of the country. Up here in the north it looks far more livable (the winter cold can't be worse than the American Midwest). Transportation is excellent, but it seems that part of the problem is the cost of that transportation. Using a JR rail pass (only available to foreign visitors) blinds me to the real costs of travel here. Yukiko told me last night that she grew up in Sapporo and has friends there, but she never goes because of the cost. Amazingly, it can actually be cheaper to go to Los Angeles, or to Sidney or Honolulu, than to travel to Hokkaido from Tokyo during the peak travel season (late summer). Looking outside at the countryside, pretty but showing signs of environmental strain, I'm not convinced that such barriers to travel are inherently a bad thing. I arrive in Morioka and try to check my email but am thwarted by a low battery. I plug the machine into the wall for a while but it's not long enough to get a good charge. Being an email road warrior is relatively easy in Japan (the newer gray payphones have both analog and ISDN jacks, and a shelf designed to put the computer on), but the problem of batteries remains. I'm spending too much time hunting for public phones that are within six feet of an outlet, or hanging around restrooms and other places with power while the machine gets a quick charge. My little handheld PC (a somewhat battered Casio running Windows CE) is great, though. Two AA batteries can keep me going for days. I find the train to Hakodate and we head north at a much slower pace; there are no Shinkansen trains beyond this point. We pass a town named Mukaiyama -- "facing mountains". From the windows it looks to be a nice place, with large traditional houses and open spaces. It's pretty outside, but I'm very uncomfortable today. My back hurts like hell, mostly from lifting my bag up stairs at stations, and from bad train seats, and from bad hotel beds. The capsule hotel, with its thin foam cushion, has really finished me off. Add to that the lack of a shower and the heat in this car… While waiting between cars for a toilet I fall into conversation with a couple from Hong Kong who are also traveling using a JR train pass. They are headed for Sapporo for the big snow festival. Though young looking and simply dressed (boots and backpacks), the husband speaks in the confident, almost arrogant manner of a wealthy businessman, or the son of one. Upon learning that my wife is Japanese he asks me, "so you're traveling to get away?" I struggle to think of an appropriate response, some snappy comeback perhaps, but I don't have one and he is gone. The snow is getting deeper, the trees smaller. The train throws up clouds of snow, obscuring the view. The coast, when we near it looks wild, dangerous. We pass an amusement park, its rides held firm by chains of ice. Then it's a whiteout, snow blowing. Then the sea appears again, violent and cold. I talk to an American couple with a year-old toddler. They are from Portland, Oregon. She has been to Hokkaido with the National Guard in the past, and now they are also coming for the snow festival. It seems everyone on this train is going to the snow festival. I had heard about it, but hadn't based my decision to go to Hokkaido on the event. In fact if I had known that I would be riding a train for over six hours that contained nothing but other foreigners going to a festival that attracts tens of thousands of others of our kind, I might have chosen another direction to go. But the Winter Olympics are beginning in Nagano in mere days and Japan is quickly filling with curious foreigners. This is not the best time to try being a solitary adventurer. We pass through another town, a place with many houses but no life evident. The streets are under at least two feet of snow. There are no tire tracks, no footprints. It is a near- blizzard out there. Hakodate When traveling, there often comes a point when your mind and/or body temporarily give up, lose resolve or just cross a threshold from "tired" to "exhausted". The nice thing about traveling alone is that you can push yourself until you reach that point, then deal with the resulting collapse on your own schedule, and not have to suffer through somebody else's episodes when you yourself are energized and ready to go. Of course there is a downside: the miserable seek companionship; without it, discomfort can be a lonely experience. My down time started about 30 minutes before arriving in Hakodate. I was on the train, catching up on notes and looking at the scenery, when I suddenly came to the realization that nobody in the train car was Japanese. It had been an eight-hour trip (first the Shinkansen, then an express to Hakodate) and I had met a number of people: the couple from Portland with their baby, another couple from Australia, a family from Hong Kong among others. But all the Japanese had exited long before or were in other cars. (Was it just a coincidence that all the JR rail pass holders were in the same car? Or was it perhaps JR's mistaken belief that we foreigners would want to share the company of other foreigners?). Everyone in this car was looked tired, and all (by this time including me -- I needed some fun) were headed to the same place: Sapporo for the big snow festival. This in itself didn't bother me (I have no problem with people from Australia, or Hong Kong, or Portland), but I was sticky-hot (the temperature in the train was way too high, and I hadn't had a shower in the morning), sleep-deprived, and my back was hurting in a bad, bad way. I was also feeling a bit alone. The Australians were entertaining ("I gotta have a smoke, mate, how long you figure we'll be stopped here?") and the baby from Portland cute to watch as it toddled around from person to person. But suddenly I felt like just another worn-out tourist, suffering through some guidebook adventure to say I was there. The novelty of propping the computer on my knee while standing in the train's restroom to get a little more juice from the single outlet to type one more paragraph had long since lost its appeal, and my handheld PC seemed to have run its AA batteries dry-cell dry. The Aussies said they were going to stop at Hakodate for the night, and had already made reservations at a cheap place listed in the Lonely Planet Guide (what else?) with a name like "Nice Day Inn". "Run by a guy who speaks English," said Mr. Aussie. "I think he's American. Cheap place, only $30 a night." Sounds swell, I thought, but I wrote down the phone number anyway, just in case. I had already decided to stop in Hakodate to avoid scrambling in the evening to find a too- expensive room in Sapporo. I gathered up my books and bags, stashed the Japanese language workbook I'd been scribbling in and got off the train. There was packed snow on the platform and my shoes were slippery. After a few steps I lost my footing, and while stumbling to catch myself from falling felt that awful lurch at the bottom of my spine that says "you've had it". The hours on trains, the standing in lines, the discomfort of the capsule hotel -- all combined in one big spasm of lower-back agony. I waddled into the JR tourist information center and asked about hotels in the area. They had a list of room rates; the nicest hotel, right in front of the station, listed at 13,000 yen. The cheaper business hotels were listed at around 7000 yen. The "Nice Day Inn" was conspicuously absent. I looked with longing at the big Harbor View Hotel just a few steps away. The young woman behind the counter said, "choto mate (just a moment)", rummaged through a folder, then produced a discount coupon: Harbor View Hotel, including breakfast, 7700 yen. My luck was changing. As I left the tourist information center I noticed a small group of young travelers, backbacks slung over their shoulders, consulting their Lonely Planet Guide. "Have a Nice Day", I mumbled at them. I checked into the Harbor View, feeling better by the minute as I was ushered here and there, bags carried for me, yukata laid out on the bed. I took a long shower, then a bath and lay on the bed for a while with a pillow under my back, enjoying my seventh-floor view of the Hakodate Ropeway going up and down its cable on the mountain south of the city. The sun went behind the hills to the west. I called Satomi in Kagoshima, and she suggested I pay for a massage. A card on the desk indicated that the hotel could arrange one for about $30. It seemed like a bit of a splurge but she urged me to do it. I called and scheduled it for ten o'clock, then went out for a walk and some sushi. Later, it was nearing ten o'clock so I decided to clean the place up a bit. My clothes were hanging all over the room (airing out after a quick steaming in the bathroom) and I already had books and papers scattered everywhere. I spent five or ten minutes putting things away before the appointment. At ten sharp there was a knock at the door. The masseuse was a thin middle-aged man with strong looking arms and a white uniform. He had a small bag and a strange demeanor; he bustled in, talking too fast for me to catch anything and, strangest of all, he never looked directly at me. Soon I understood why: he was totally blind. I was made to understand that I should wear the yukata; he worked on my back, legs, neck and upper arms through the fabric, using fast and firm presses with his thumbs and fingers. This lasted for 40 minutes without a break. By the time he was done I was totally, utterly relaxed, and the pain was nearly gone. The next morning my back was hurting again but I arranged my bag, responded to a few emails, then went downstairs for breakfast. I reluctantly turned in my room key and considered what to do. At the station, the JR information people told me that the train ride to Sapporo would take three and a half hours, and that it would leave every two hours. I couldn't yet accept the thought of sitting on another train for hours on end, so I decided to take a walk first. I went back to the hotel and stashed my bag and computer in the front lobby. There were a group of Russians arriving, looking very Slavic in their leather jackets, fuzzy hats and big overcoats. I hung around for a few minutes, warming up before going back into the blowing snow. Every time I took a few steps -- in any random direction -- my movement triggered the smiles and bows of the hotel staff. I missed the place already. What I had intended to be a half-hour walk stretched into two hours, then three. The walking seemed to be curing my back problem, and I couldn't get enough of Hakodate. It seems a perfect city: perfect size (you can walk from one end to the other in 40 minutes), perfect views, perfect mix of small shops and larger department stores and offices. And unlike Tokyo and Osaka, there are attractive houses here, and quiet streets. And there are huge old temples -- not museum-piece temples with ropes, signs and informational brochures, but real working temples with school buildings and people. And there are big Greek and Russian Orthodox churches -- Hakodate, like Yokohama and Nagasaki, was one of the first port cities opened to trade with other countries, and for generations it had been the gateway to Russia for Japanese goods. I rode the Ropeway, I sampled pastries in the basement of the big department store, and I poked around the central market. I practiced my Japanese: the natives were friendly. By this time the snow had stopped and it had warmed to just above freezing with an occasional flash of sunlight. Finally I passed a brew-pub and a touristy but tasteful little mall (European themed), and I found my way back to the station to purchase the Sapporo ticket. At the station, another group of Lonely Planet travelers were gathered, seeking the company of other Lonely Planet travelers and talking about their adventures while they waited for the next train. They looked tired; in fact they looked determined to be tired, determined to make the journey into The Journey. I wondered if I looked any different. I stopped short of the reservation desk, looked back through the doors at the Harbor View Hotel, and I gave in. Sapporo could wait. The desk clerk didn't seem surprised to see me. "Same room?" he asked. Nice Day I begin to understand the city of Hakodate more fully on my second day. The rail tunnel built in the late eighties between Honshu and Hokkaido made a direct route to Sapporo possible, with no need to ferry across at Hakodate. At around this same time, the timber industry in Hokkaido was nearing a close with little left that could be profitably logged. Hakodate's importance as a port city was in steep decline. What to do? With a city rich in cultural heritage and with an abundance of historic buildings, and with a summer climate and terrain perhaps unmatched anywhere in Japan, the answer was obvious. Hakodate, in the space of a decade, was converted into a tourist destination. Walking the snow-muffled streets, seeing the old brick factories and warehouses now containing small shops and trendy, but quite empty restaurants, riding the ropeway... it's very pleasant in winter, but easy to imagine the busloads of tourists that must fill this city in the warmer months. Some of Hakodate's charm fades when one imagines it in summer, but I have to wish them well in their economic conversion. There are certainly worse things that can happen to a declining city. I'm walking along an older, undeveloped part of the waterfront, and I approach a parked car from the rear. Its engine is running, steam rising from the tailpipe. A man sits alone in the front seat, flipping quickly through a pornographic magazine. While riding the ropeway and taking in the view from above, I find I am completely smitten by the city. I have an unusually warm feeling about the place, and it all comes together when riding back down. The operator is friendly and smiling, and we are alone together in the car. It is quiet, and the low humming of the cable mixes with a gentle scent of perfume. Snow swirls outside and we are a hundred feet off the ground. "Very pretty," I tell her in Japanese, leaving the comment ambiguous. "It is best at night," she replies, looking outside. The sky darkens early, and I continue my walking. Lost in a back-alley, I come across a heavy-looking brick building with a tile roof, European in architecture and heavily draped in icicles. I approach the building from the rear, and can hear a roaring sound from inside, like a furnace. I also hear loud music coming from a high open window. Orange light streams out with the music. At the front of the building there are sliding doors, open just enough to slip through. Curious, I go inside. The glassblower I at first assume to be a student, or apprentice. She is young, with her long black hair tied messily behind her head. But within seconds I can see that she is no beginner. She is petite but her arms are tough, muscular. She and her gaffer move confidently and quickly, moving and shaping the glass, transferring smoothly from oven to punty then shaping, turning, cutting and forming. I watch as three pieces are born, and one is lost to the hard floor. Watching a blow is like watching modern dance. Every move is planned, but there is an element of surprise, a feeling of at-the-moment reinterpretation as a lump of hot glass evolves toward a finished piece. There is little talking over the noise. The blower wears a brightly colored and baggy T-shirt, the sleeves torn off, exposing her shoulders. Her jeans are thick and baggy, rolled up over heavy boots. Her hands and arms are a mess of black soot, and the smell in the shop is pungent. I watch, fascinated. When they finish the blow there is no hesitation; the fires are shut down, the boxes and brooms are brought out, the lost piece swept away. The gaffer glances at me and nods a greeting. I slip back out the door and into the snow. I'm hungry and decide to try the brew-pub. The pub is the real thing: big shining kettles and pipes, fancy woodwork, big glasses, the works. I'm shown to a seat at the bar and given a menu. Then I notice, a few stools down, the Aussie couple from the train. "Hey mate!" says the Aussie guy, whose name turns out to be Matthew, "We thought you was going to Sapporo! Have a beer with us, hey?" We shuffle bar stools and I ask what happened to their own trip to Sapporo. "Couldn't get a bloody room," Matthew says, "place is booked up solid. Nice Day again tonight, then we'll go up in the mornin'." So what about the Nice Day? Karen chimes in: "Nice bloke runs it," she says. "Bit cramped though." Matthew concurs, "We're in a small room with two other folks. Nice people, you know, but..." Karen continues his thought, "but a bit of a line for the toiley..." "But cheap!" finishes Matthew. Half a beer later (surprisingly good, thick ale), a group of three young women come in, stamping snow off their boots, and join us. They are also Australians, part of the group I saw at the tourist office earlier in the day. Small world... or is it? Matthew has his Lonely Planet Guide open, showing me the hotels he's tried to call in Sapporo. I asked him if this pub has been written up in the Guide "Yeah," he says, "Everybody comes 'ere I'd guess". It turns out everybody also goes to the sushi place down the road that Matthew later suggests we try. The food (color-coded plates of rice and fish that travel around the room and past the diners on a stainless steel conveyer belt) is cheap and tasty, the waiters friendly, and four booths away sit four of the Chinese I met on the train the day before. "Hey," yells Matthew, "right fancy seeing you here!" Leaning forward and speaking to me in a half-whisper he says, "Smart bloke, that one in the green shirt. Speaks four languages." "Don't tell me," I say, "Nice Day?" "All of us!" he says proudly. I learn a bit more about Aussies in Japan over the next hour. Matthew and Karen are from Sydney via Ayers Rock ("…Small place, okay really but everybody knows who's bonkin' who within an hour, you know?"). They are doing a bit of traveling while waiting for word on some kind of job in Tokyo. "Hospitality," said Matthew. "Good money in hospitality." He doesn't elaborate. Of the three young Aussie women, one is working at a restaurant in Shibuya, and teaches English on the side. Her two friends are up from Sydney and are also looking for work. One of them seems a bit overwhelmed by the snow. "How do they clean it up?" she asks. "Must be an awful mess when it melts." "Drinking Dinner" Katsumi suggests we go for a "drinking dinner". I describe my trip to Hakodate, and he has many thoughts to share... Most of the Japan coastline, from Hokkaido to Kyushu, has been destroyed by useless reclamation projects, he tells me. "It is so stupid, I can't stop my anger," he says. "When I was young, I could go to the sea and there were tide pools, octopus and sea eels for breakfast, catching razor clams with salt." He shakes his head, "My son Kaoru will never experience these things." He goes on: "If I were prime minister, and this is 100 percent not possible, I would tell the corrupt construction companies that they have twenty more years. We will give them the same amount of money -- but to repair the damage, not to create more stupid 'reclaiming' projects. After that the construction companies need to find something else to do… "…Japan is run by technocrats. There is no effective central government to keep them under control. In many ways I respect the Meiji era. The Koreans will say it was a terrible time, very cruel. But it is also true that without Meiji government, Korea would be part of China now, like Tibet. All world history would be different. America would be fighting Russia, not Japan, in World War II. The Russian revolution would have failed because the Russian army would not have been fighting Japan. Japan -- and the rest of Asia -- would just be imperial colonies, like Africa." On China and Nanking: "…It is not the Japanese, it is humans. Look at what the Chinese do today to Tibet and Mongolia. No one can challenge them except America. All Japan can do is bow and say 'I'm sorry' and publish self-criticizing books. No Japanese government now has the strength to say that these things are no way related, that more than fifty years have passed." On Japanese cultural decline: "…Television is just cooking and eating shows for last five years. It is like the end of the Roman Empire. Japanese media have completely given up their responsibility. Just stimulation, no difficult subjects." "…Japanese are the Italians of Asia," says Katsumi. I ponder this last statement. Yes, perhaps there is a similar fondness for noodles and squid, and an overt sexuality (displayed most boldly in train station and magazine advertisements, and on the streets at night) contrasting more generally conservative values and historically strong (but now dramatically weakened) religious roots. And there is the Japanese mafia, the Yakuza... and, I think to myself, perhaps a historical tendency toward facism? Osaka Takeru is the ten-year-old son of our friends in Osaka. I announce plans to travel up to Kyoto for the day and Takeru surprises his mother by asking to go with me. He turns out to be a real help with the subways and trains. If this were a Kipling novel he would be Kim, steering me from trouble while boyishly kicking stones down the street. Kyoto is quite unlike other Japanese cities, and was left essentially undamaged by the bombers during the war. The city is an interesting mix of the very old and the very new. In Kyoto we meet up with another friend, Hiroko, who is preparing to enter Tokyo University's medical school. Hiroko expresses the opinion that many wealthier Japanese who have traveled or lived abroad are now seeing the value of preserving traditional Japanese culture, or least the outward appearances (in the form of traditional art and architecture) of that culture. Now there is more effort to preserve than at any time since the war. This reminds me of a conversion with Katsumi. I had been walking through a district of Yokohama that was historically an area where foreigners (mostly English and Americans) had lived after the war. This prime real estate, perched on a hilltop south of downtown, was now increasingly the district of choice for very wealthy Japanese – in particular the beneficiaries of Japan's "bubble economy" of the 1980s. Katsumi referred to these new rich as baburu shinshi, or "bubble gentlemen". This new class of citizen (also common in America as a result of high-tech industries) possessed wealth far in excess of the average Japanese, but lacked the cultural refinement to apply that wealth in a tasteful way. The result is often a large home of non-traditional design, completely out of character with the surrounding area and stuck incongruously in the middle of an otherwise attractive neighborhood. The bubble gentlemen had their good years -- but their fortunes have now collapsed along with the Japanese real estate and stock markets. Perhaps the more traditional arts are beginning to take their proper place alongside golf and tennis in the minds of those who retain more conservative ideals – and held more conservative investments. Hiroko is a good guide to modern Japanese culture. Unmarried, well educated and well traveled, she has worked as a midwife, has spent a number of years living in America, and has now been accepted to study medicine at Japan's most prestigious university. Hiroko talks about Japanese families. For Takeru's benefit we eat at McDonalds, and Hiroko describes the Japanese concept of "children held together by children". The avoidance of divorce by de facto separation in one example of this, with husband and wife living essentially separate existences within the same small home, and more frequently the husband taking up virtual full time residence at his office and/or his favorite bar or, in more extreme cases, in his mother's house. There are other aspects of this as well, according to Hiroko. For example, a new son-in-law will have little respect from the wife's family until he becomes the "father of the grandchildren". At that point his status may well be elevated to a point above that of the daughter he has married, even within the wife's own family. (The converse of this does not seem to be true, however; in a change from the American mother-in-law stereotype, many Japanese daughters-in-law find that they can never meet the expectations of their husbands' families, and in particular of their mothers-in-law.) Exploring more of Kyoto's oldest districts toward the end of the afternoon, we see two maiko (apprentice geisha) depart a limousine and enter a narrow gated passage in the front of a low, darkly stained wooden building. Hiroko is impressed: "You are very lucky, this is rare to see." A Mercedes Benz pulls up soon after the two maiko have entered the passageway. Many older doorways in Kyoto are like this, Hiroko explains, because the city in old times would tax properties based on their street frontage. Kyoto is a city of winding streets, dark passages, and mysterious temples hidden behind mysterious walls. Seen on the train back to Osaka: an older, conservative-looking gentleman is carrying a small black bag, like a book bag or soft briefcase. Like many such products, this bag has a trendy-looking English logo sewn on the front. The logo on this bag is the word Bitch, accompanied by a small graphic showing two characters representative of the international symbol for male and female, like you might see on a restroom door. In this graphic, the silhouetted male figure has one arm up, holding a gun to the head of the female figure. In the evening we are back home and Takeru is very tired. I sit with Kiyoharu and Yoko on the floor around a low table, drinking tea and beer, eating rice balls and watching television. There is a documentary being aired. In it, a small group of Japanese tourist/adventurers, having the appearance of a middle class family on vacation, are somewhere in the dark depths of Indonesia, in Borneo perhaps. I have trouble following the "plot", but it seems the family from Japan has trekked to this remote village, with their new nylon packs, mosquito netting and freeze-dried food, to experience life in a primitive Indonesian village. They have brought pictures of Japan, toys for the native children, and manage to teach some of the Indonesians a bit of Japanese. The tone of the documentary is set by a fast-paced commentary with laugh track and calliope-style music. I understand very little of what is said, but the laughing tells me all I need to know: the camera cuts to a soiled young native Indonesian stuffing live, squirming larva into his face. The camera cuts to an equally young Japanese girl squealing with shock and amazement as a handful of the grubs are offered her way. Fast forward: now the family of primitive Indonesians has been given "modern" clothes to wear, shoes for their feet. They are all boarding a JAL flight to Tokyo. Look, they are riding the Shinkansen. Look again! Look! Look! They are riding a roller coaster, they are trying to play golf, they are eating sushi! But eventually they become homesick, and they return back to Indonesia, assuming their previous lives but having seen for themselves what the "outside" looks like. I think back to Katsumi's comments about Japanese television. Perhaps he is right. Perhaps this really is what cultural decline is like. Seen on a shopping bag in an upscale Osaka shopping mall: "Diet butcher skin thin". Yoko is up late as usual in Takeru's room (Takeru does not sleep in his own room, preferring instead to sleep with his father). Yoko is reading and writing emails most nights; tonight she talks with me, and tells me of her "secret business". It seems that Yoko is managing a small-scale operation for Kiyoharu involving the subcontracting of metal stamping work. With the language barrier I have some trouble following the trail of labor, money and finished components, but it seems that a small number of Yoko's friends have been provided with compact stamping equipment with which they produce small rings of stainless steel. These rings are subsequently heat- treated for use in automotive air conditioning units and other applications. The average part-time income for this work is 40,000 yen per month, or about $350. Yoko shows me her little notebook with the figures. Yoko claims that the large customers of Kiyoharu's company have no idea where these parts are produced. The cost of this method of production is dramatically lower using more highly paid (and presumably higher skilled) factory employees, and the company banks the profits. The whole operation (and I suspect Yoko does not know how large an operation she is part of, or how common the practice probably must be) is clearly intended to get around strict Japanese labor laws and allow the company to operate with lower labor costs. Is it legal? Most likely not: the finished parts come via a tapping on the window at night, and are left in unmarked blue plastic bins under the front window. I stay up with Yoko for a time, then return to the guest room and turn on the TV. Japan's winning performances in speed skating and ski jumping are played endlessly, it seems. The reruns put me quickly to sleep. (Postscript: nearly a year and half later I came across an old news item, from a larger article in the December 23, 1996 issue of Newsweek: "…Under pressure from citizens' groups, the [Japanese] Patent Agency in September rejected a trademark applicant who wanted to print a T shirt with the word BITCH above a picture of a man holding a gun to a woman's head.") Kagoshima Kagoshima is a port city, located on a horseshoe-shaped, protected bay that is dominated by a large and active volcano. The volcano, Sakurajima, emits a constant plume of gray smoke. Larger eruptions of dark black ash are a near-daily occurrence. Amazingly, the small island on which the volcano sits is occupied, with small villages scattered around the sloping coastline. One morning I take a long walk down to Kagoshima's industrial waterfront. The waterfront here is ghastly, lined with toxic-looking small industries and concrete bulkheads. There are automotive and marine repair shops and small manufacturing companies. A large scrap yard leaches red-stained effluent into the bay. The sea has been pushed back, reclaimed by seawalls and tetrapods. Small fishing boats, stained and listing, are tied on lines strung between mooring buoys and the concrete shoreline. There is filth floating on the surface of the water, and filth lining the shallow bottom. It was not far from here, in Minamata, that one of Japan's worst environmental disasters occurred. In the years 1932 through 1968, a large Japanese chemical company, Chisso Corporation, dumped as much as 27 tons of mercury compounds into Minamata Bay, in an area used extensively for sustenance fishing by the local populations. This dumping was carried out legally, but its effects were devastating. By the time the dumping was stopped (nearly ten years after a problem had been identified), more than 3000 people had been sickened and permanently disabled (or in many instances killed) by what came to be known as "Minamata Disease", or mercury poisoning. Chisso Corporation's response to the discovery of the cause of Minamata Disease was a classic and tragic example of corporate greed. Rather than acknowledge the problems and stop the dumping, Chisso Corporation spent ten years disputing the obvious data, muzzling its company medical staff (who had originally made the link between mercury poisoning and the observed symptoms) and quietly making nominal cash settlements with uninformed citizens (most of who worked for Chisso and were therefore unable to refuse) in exchange for their agreement not to pursue more appropriate compensation. And during this ten years, Chisso continued to dump, pausing only long enough the change the dumpsite to a nearby river where it poisoned a different (and presumably less-informed) local community. Environmental disasters such as the Minamata poisoning are less common today, but Japan still has a dismal record of protecting its own shorelines. It seems the country is well positioned to lead as Asia becomes dominant in the world economy. Japan has the intellectual capital, the experience and the geographic advantage to remain an economic superpower. But Japan's challenge will not be purely economic or technical. It will be environmental as well. The country has been systematically trashed in the space of 100 years. Although Japan is an efficient user of energy (those of us who drive oversized cars, live in oversized houses, and continue buying and discarding useless consumer goods have little to say in that regard), but its record of environmental protection is not good. Perhaps Japan's next great awakening -- its next restoration --will be to understand what has been lost, and to work to bring it back. In the afternoon, near the Yamaoka's house on the hill we encounter a sweet-potato vendor. The vendor drives a small Honda truck with a blaring loudspeaker. His deep voice sounds like a Muslim call to prayer. The rear bed of the truck is filled with a huge steel roaster built of welded steel. The vendor pulls out two sliding racks and we choose a few piping hot, blackened lumps. The potatoes meat is colored a vivid purple, and is delicious. Sound trucks like this add to the aural clutter of Japan. Jingo tunes are everywhere here, from the reminder tunes on the trains and the electronic folk tune that plays when it is safe to walk across the street, to the loud, distorted music of a kerosene vendor's truck. These hundreds, or thousands, of familiar tunes must feel a great comfort to the traveling Japanese returning home from abroad. Electric Water In Kagoshima, Satomi's father invites me with him to his favorite onsen (public bath). In the entrance/changing room there is a Meiji-era drama on a large television. Why are so many Japanese daytime dramas set in the Meiji era? I think about what Katsumi had said, about the Meiji era having many "good things". Does Japan today yearn for the strength and confidence of that imperial era? It is rather like Russians looking back with cultural nostalgia on the Tsarist years. In the bath, I'm introduced to a variety of older men. Some are important company managers or executives, while others are simple laborers. In the baths, the veneer of dress is stripped off. I'm directed to sit in the "electric water", which turns out to be exactly what the name suggests: electrical conductors extend a few inches into a narrow section of the hottest pool. When I lower my body between the conductors I am immediately in pain from the electric shock. The current passing through my body causes my lower back to spasm, and a severe pain shoots up my spine. Immediately I'm out of the pool, watching in amazement as seventy-year old men take turns relaxing, apparently without pain, in the spot I've vacated. One man, looking at me with a smile, moves closer to the electrodes until he is actually touching them, taking the current directly. Later in the day, Satomi arranges a home visit by a local chiropractor. He is a strange character, but very funny according to Satomi. He wears an old-fashioned doctor's smock, like you might see an orderly in a psychiatric ward wearing in an old movie (Harvey, perhaps, with James Stewart). This man is very strong, and before starting in on me he demonstrates his strength with a series of one-armed pushups and other exercises. From the feel of it, he is attempting to somehow break and then somehow repair every bone and joint in my body. When he gets to my hand, he spends a many minutes working on the large joint of my thumb, the one I had wrenched when skiing in Shiramine. I have not mentioned the thumb, but somehow he can tell that it has been recently injured. The torture goes on for thirty minutes; it's amazing that my back (which has worsened to the point where I have trouble getting out of a chair) can survive the bizarre poses he bends me into. (There is a sound like corn popping when he twists and jerks my spine.) But his efforts seem to do no additional damage, nor do they so much good. By the next morning I'm in pain again. Kumamoto With a day to spare and no plans, I decide to take a local train to Kumamoto, an old castle town in the south center of Kyushu. On the train's route, south of Akune, I glimpse a pristine shoreline, painful in its rugged beauty, as yet untouched by the technocrats. But near Akune the view changes again: more tetrapod breakwaters, more seawalls, more ugliness and industrial clutter. But some of the smaller towns we pass show a better balance, having the look of fitting themselves to the shore, rather than forcing the shoreline to fit to them. North of Akune there are more trees, and more attractive towns. The weather is misty, not warm or cold. It feels much like home in the Seattle area. I get off train, after a one-hour ride, at what I believe to be Minamata. But the station is not close to waterfront. I walk for thirty minutes toward the water, but eventually I realize that this is not Minamata at all. A man in a suit stands and pisses in the center of an empty parking lot. I go back the station and look at the signs again. I have been walking aimlessly through Izumi, a non-descript town that's only claim to fame seems to its crane park, a small compound with a tepee shaped visitor center. I board another train and continue north and west. Katsumi may have been right when he stated that an unbelievable fifty percent of the coastline was now "reclaimed" with seawalls and erosion control projects. This should be the most unspoiled part of Japan's coast but here as well bare white concrete forms a new shore. No tide pools, no sand, no wave-washed rock cliffs or pebble beaches. Perhaps these things still exist here, hidden behind headlands, on inaccessible points of land out of site, but if they are here I cannot see them. On the train, a group of rumpled Kyushu businessmen in white shirts and ties pour drinks from a bottle of sake. They are animated, trading private laughs about some adventure the previous evening. It is Saturday morning. Kumamoto turns out to be another noisy, grubby little city with little charm but plenty of car exhaust. I visit Kumamoto Castle, a large complex of old (1607) Edo-era fortifications. The impressive and original stone walls of the castle are capped by an uninspired reconstruction of the huge castle building. This reconstruction has replaced classic woods beams and delicately carved stairs with massive pours of reinforced concrete and synthetic veneers. The effect is something akin to the plastic food displays outside the restaurants nearby. It is a testament to the four hundred year old castle walls that they are capable of holding up this massive structure. I leave the castle and, before boarding the train back to Kagoshima, stop at a brew pub across the street from the station. The pub serves good ale, and I order an expensive plate of cheese to complement my pint of bitter. For four soda crackers, five Ritz crackers and a small piece of soft cheese I pay four dollars. Kameta I go with Satomi and Satomi's brother Makoto to Kameta City, where they are visiting a friend near a hilltop sports complex. The sports complex itself sits in a large, grassy park on a high hill, away from any city. It is quiet here. Alone, I take a walk down some old- looking stairs behind the complex, and soon find myself in a quiet suburb of nice old and new houses. Some of the homes are quite large, with impressive garden entries and rustling bamboo hedges. Soon I stumble across a temple, Kameta temple as it turns out. It is very old (originally built in 1568, then rebuilt in the late 1800s after being ruined in an eruption of Meiji era violence). It is very quiet. At first I think there are not people, then I realize that there is a monk meditating, silent and still, in the glassed-in room of a side building. As I watch from across a courtyard an old woman emerges from another building. She is holding a tray with tea. The monk stirs, leaning forward to open a sliding door and accept the tray. I stop and talk briefly with a bent old woman tending flowers at a gravestone. She asks me where my home is, I tell her Seattle, America. She is animated, telling me (as best I can translate) that her son made a trip to Canada. She mentions Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal. She is thick, wrinkled and sun-darkened. She has the air of matriarchal authority, and the marks of a ready and frequent smile around her old eyes. I move on. Soon I am seeing the layers of Japan's recent history in the walls, and the steps and stones of the temple grounds and the surrounding suburbs. Old chiseled stone marks Edo period, or before. Pushing through the bamboo, I find old stone monuments nearly lost, forgotten in the thick brush. I find late Meiji era in the carefully cast foundation walls, built up from rigidly formal mortared blocks. And finally, I find modern Japan in the reinforced concrete of medical clinic, in the architecture of a small coin laundry, in the sports complex. It is all here in the buildings. I buy an orange soda from a vending machine and walk back up the hill. At the sports complex, I'm nearly run over by a Nissan Skyline sedan with lowered suspension, darkened windows and a loud exhaust. Sakurajima We take a car ferry across the bay to Sakurajima Island, where the volcano sits and waits for its next eruption. It is an agreeable island, with crumbly pumice soil and a crinkled lava shoreline. It is afternoon, and children are walking home from school. The children wear yellow construction-style hard hats (presumably to protect them from the rocks that sometimes fall along with the ash during eruptions) and carry large red backpacks. Along the road that rings the island, every few hundred yards, there are strong-looking eruption shelters. On the slopes above there are lava dams by the dozen, and more under construction. On the shoreline below the road there are beautiful small inlets with long fishing boats, shaped like large skiffs and carrying short mizzenmasts with stabilizing sails on their sterns. Across the bay, protecting much of the Kagoshima waterfront there is a huge breakwater. It is a mile or more long, 60 feet wide, and fronted by thousands of concrete tetrapods. The breakwater is intended to stop the massive wave that would inevitably be produced as a result of major eruption. But looking up at the insignificant concrete lava dams that scar the massive sides of Sakurajima, I get a perverse pleasure imagining what this mountain could do regardless of the grand development projects intended to control it. Looking at the huge mountain, with its constant rumbling and plumes of ash, I can't help but think the huge lava dams are nothing more than another public works fiasco, intended not to protect the population so much as to protect the existence of some politician and his construction company campaign contributions. The scars across the mountain seem like only scratches, of no significance if the mountain were to really blow its top. Ibusuki We take a short trip to Ibusuki, near Nagasaki-bana. Kaimon-dake mountain represents the most southern place in mainland Japan. The small and perfectly conical mountain looks like something from a Polynesian movie. But Nagasaki-bana itself is a tourist trap, even in the off-season. Busloads of old people follow flag-bearing guides wearing stewardess-style uniforms with white gloves. A bus driver practices with his golf clubs while he waits for tourists to return. There are dead, stuffed sea turtles for sale here in the shops, and turtle belts. A sign in one shop states that turtles bring good luck. A faded sign near the wind-whipped beach has a red graphic depicting a turtle. The sign reads: "Do not collect turtles. It is illegal." Fishing boats work the waves, close to the breaking surf. The wind is up and the boats rock, their small mizzen sails flapping. There are tidepools here but they are empty save for a few cigarette butts and empty Pocari Sweat cans. On the drive back we stop at a sand onsen. Makoto and I lay buried in hot black sand under a bamboo shelter, listening to the waves crash on the black beach. Women laugh as they shovel the sand, making spaces for other guests and re-burying our toes when we wiggle them free. It is a spectacular location at the base of a cliff, with a view of rock outcroppings, volcanic and dark against the cloudy and gray sky. Down the beach I can see more concrete tetrapods stacked in miles-long bulwarks. Why? Izumi It is wedding day for my sister-in-law, Izumi, but there is surprisingly little tension in the air. Satomi and I, with Julian, drive with Satomi and Izumi’s father to the photography studio, where pictures are taken of Izumi and her husband-to-be, and with her family, and with his family, and with extended families. (And how different from when Satomi and I married in Seattle: for us there were no cameras, no hovering families; just a quick speech by a judge and the signature of two friends brought along for the purpose.) This is going to be a low-key wedding. Most members of Satomi’s family are Jehovah’s Witnesses (surprisingly, there are many Witnesses in Japan), and elaborate celebrations of personal events (birthdays, weddings, funerals) are frowned-upon in this faith. The wedding ceremony is held in a meeting hall of what appears to be an office building, or perhaps a small convention center. The room is starkly lit with fluorescent fixtures. There is a large white board at the far end, and a stand-up lectern. A small foot-high stage has been brought in along with a simple display of flowers. We sit in folding metal chairs and listen to a series of speeches. A church elder drones on, but I can only pick out a few of the biblical references. The theme is 1st Corinthians (chapter 3?), a bit of Genesis, some Ecclesiastes, "…however, she must respect..." The Jehovah’s Witness faithful refer to themselves as “JW”. This is a sect full of important, self-identifying keywords: its members are “brothers” and “sisters”, and to be labeled “worldly” is not a compliment. The JW faith has been very successful in Japan, with its biblical conservatism (they are literalists), strict dogma and religious exclusivity (all other Christian sects are viewed as products of Satan) combined with a surprising amount of cultural and racial diversity. (The latter element is immediately apparent at any large JW gathering in the states. I may have a strong dislike for their dogmatic beliefs, their xenophobia and their propagandistic materials, but I have to give some respect to any faith that manages to bring so many races together in one place. This is unusual for American christianity, which more often worships their God in de facto racial separation.) In my limited experience, JW sermons can be tiresome in the extreme: blissful descriptions of paradise follow dire predictions of the coming Armageddon, while violent biblical imagery is somehow related to the love of Jehovah. Fortunately this particular sermon is in Japanese so I can’t be offended by the rhetoric, only bored by it. I fidget in my chair while others flip through their JW bibles. My mind wanders and I have impure thoughts about a sister two rows forward who wears a flowing silk blouse, matching skirt and knee-high leather boots. Satomi, for no reason I can see, pinches my leg. Later there is a formal dinner at a typical (but perhaps slightly low-rent) Japanese wedding hotel. The two families sit on opposing sides of a rectangular room, staring at each other across the open space between two long rows of tables. At one end of the room the bride and groom sit -- not close enough to touch, or even to converse privately, with their own long table forming a connection between the two sides. Everyone is rather stiff and formal, at least until the beer and sake start flowing. It is a “course dinner”, with plenty of time between plates to toast the bride and groom, introduce each other and trade jokes and stories. An old man, quickly drunk and apparently the groom’s grandfather, takes the karaoke microphone that has been provided and sings an old Japanese folk song. His family seems a bit embarrassed, perhaps because expressions of any traditional (meaning Buddhist or Shinto derived) culture might be seen as going against the ideals of the faith. His voice is coarse but the melody is firm. At least one thing can be said of the Witnesses: they know how to drink. The bride and groom are drinking orange juice, but many others in the wedding party are soon feeling no pain. The groom’s mother and father are putting away enough beer and sake to make up for the newlyweds’ discretion. (You can give me a JW wedding over a Mormon event any day. The Witnesses keep it short, to the point, and know how to have fun.) Izumi has changed out of her kimono now and into a long velvet outfit. Her hair is wild from being tied up and it tumbles off her shoulders, black against the red of the dress. She is astonishingly beautiful. Much later I see a formal portrait of the extended family, taken the day of the wedding. Everyone is serious, perfectly primped and posed, with one exception. I’m in the upper-left corner, in a light-colored off-the-rack suit, holding a squirming child and looking very uncomfortable with a crooked and false smile. I’m Zelig, mysteriously appearing in the frame, out of place and utterly comical.

|