|

(Note: pictures from this trip were scanned from 35mm slides taken either

on Fuji Velvia or Provia slide film. The slides look great, but the

scanned images lost some of their sharpness. I either need a new slide

scanner or I need to abandon the use of film and go all digital...)

In the fall of 2001 I started daydreaming about taking a week off, using some frequent flyer miles and going on a selfish trip, just by myself, to someplace I'd never been before. Idle thoughts, mostly... but then I finally mentioned it to Satomi, and rather than pooh-pooh the idea she suggested I go while her sister Chiemi was visiting us. In my daydreaming I had narrowed it down to Peru, Bolivia or Ecuador. I also considered Argentina or Chile, but it seemed like I'd need more than a week to go to either of those places, as there's just too much to see. Peru sounded interesting (Machu Pichu, Cuzco). But I gathered it was the rainy season there. Bolivia (Lake Titicaca, La Paz, etc.) also sounded interesting. But the more I thought about it, the more I liked the idea of Ecuador, and the highlands in particular. I think the main reason I chose Ecuador is because, of all countries in South America, with the possible exception of Surinam and Guyana, it was the country I had read the least about. I knew it had some big mountains, and I knew its capital was named Quito, and I knew that Guyaquil on the coast was a crime-ridden port city. But unlike Peru and Bolivia, I had read nothing of its political or cultural history and had few preconceptions about the people who might live there. It was a place that never seemed to make the news. I bought a guidebook or two and a map, and I started searching the Web for accommodations. When doing one search I stumbled across a place called Hosteria San Jorge, and something about the place appealed to me. I sent an email and got an answer right from the owner, George Cruz: "David! Hi how are you doing! My name is George, the owner of Hostería and your new friend in Quito´s foothills!" George was nothing if not enthusiastic... After a few more email exchanges I arranged to stay at his Hosteria for the first few days of the trip. I also exchanged emails with Alfonso Tandazo at Surtrek, a Quito-based agency, and arranged an "acclimatization" trek leading up to a climb of Cotopaxi, a large (over 19,000 feet) mountain south of Quito. The last two days of the trip I left open, figuring I'd have plenty of time to decide where to stay once I had been in the country for a week. Friday, January 18 "Dear david! Hi friend! How are you doing! Don`t worry I will be waiting for you in the international gate of Quitos airport at January 18, 11:39 minutes..." I left Seattle via TWA at 12:45 AM, on the redeye to St. Louis. The plane was nearly empty, giving me three seats across. I can't usually sleep on airplanes, but on this leg I managed to get three hours of rest, folded up on the seats with strategically placed pillows and blankets. At St. Louis airport I had a five-hour layover. There wasn't much to see other than an old Monocoupe once owned by Charles Lindberg that was hanging from the ceiling so I read my book ("Chasing Che", by Patrick Symmes) and caught a few more winks of sleep while slumped in a chair at a deserted gate area. I had a sandwich, bought Julian two little metal airplanes at the gift shop and then, finally, went to the gate to catch my flight to Miami. The Miami flight was nearly full; I was jammed into a window seat but enjoyed watching the scenery go by. I had never flown this route before, south and east over the gulf coast, and the landforms were interesting: first the Mississippi River, then rolling hills and finally the mangrove swamps of the bayous and the gulf beyond. Florida was flat, flat, flat. If the sea level rises by ten feet then I suppose the state will lose half its area. I had a two and a half hour layover at Miami airport, in the B concourse. What an ugly airport! It's surprising that a place so bright and sunny can have such a dark and dismal terminal. I read some more of "Chasing Che" (a really good book, by the way, that retraces Ernesto "Che" Guevara's youthful motorcycle jaunt through South America), ate some greasy pizza then got on the flight to Quito. Again the plane was only partly full so I could stretch out across three seats. We landed at 11:15PM in Quito. Customs and immigration were fast and I was out of the terminal area by 11:45. There were hundreds of people waiting outside the terminal building, all of them looking intently over one another, trying to catch a glimpse of whomever they were supposed to be meeting. Some of them had signs with names but I didn't see any sign with my name on it, or with the name of the Hosteria. Every few seconds I was approached by someone who would ask me, "Taxi?" or "Telephone?" but there was no sign of George. The plane had arrived a bit early so I wasn't too concerned, but after thirty minutes I started to wonder. I fell into conversation with a taxi driver (in English; he had recently moved back to Quito after growing up in Brooklyn) and he offered to call the Hosteria for me. He got through easily and spoke to a woman who I assumed to be George's wife. The taxi driver talked for a few seconds then hung up. "I don't think they remembered," he said, "but she said they would be here in twenty minutes." Oh well, not a problem. I stood around with my bags for a while (thirty minutes passed), deflecting various offers for taxi rides and watching the crowds dwindle as the last arrivals of the evening made their way through customs. Finally I saw a woman about my age come from the parking lot, looking for someone. She spotted me with my bags (the only gringo in the area) and made a beeline for me. Following her was an older man, late sixties perhaps. We quickly established who I was, that she was George's wife (Irina) and the older man was George's father (Jorge). Neither of them spoke much English, but no matter, we did fine with our minimal overlap of language (I studied Spanish in high school, but it has mostly dribbled away after 25 years). They led me to the parking lot and to a battered looking 1970s-era GMC van. I put the bags in the back and climbed in after helping Irina force open the dented sliding side door. Jorge got in behind the wheel, started the van and off we went. We drove north and west, away from the airport and downtown Quito, into the nearby hills and up an increasingly rutted road. It went from broken pavement, to cobbles (large river rocks placed by hand) to eroded dirt, to washboards and potholes big enough to swallow a pig. The old van coughed and wheezed, blowing great farts out its tailpipe as we creaked and swayed up the dark road. We stopped at a simple gate that blocked the road, a long wooden pole painted yellow with rocks tied on to form a counterweight. Jorge honked the horn three times, waited a few seconds then honked three times again. Finally a man appeared out of the darkness, from behind a nearby fence. He was holding a long, coiled rope. The man tied one end of the rope to the end of the pole, unlocked a padlock and the pole swung up, out of the way. We drove through and Jorge explained (as best he could), "We need... because at night is necessary." I caught his meaning. If there was one common theme to the guidebooks and travel commentaries I'd read about Ecuador, it was that petty crime is rampant. The taxi driver I had chatted with at the airport ("Mark") had said something like, "This can be a great country. Throw anything in the ground here and it grows. But the place is corrupt. The government is corrupt, and thieves are everywhere. Be careful downtown." After we arrived at the Hosteria I was shown to my room. It was comfortable (if a little cold), with a red tile floor, a fireplace made of river rock and crumbly mortar, a fine-looking bed and a small bathroom. Everything was clean, if a little out-of-kilter looking. The floor tiles followed the contours of an uneven slab foundation and the furniture -- the bed, the chairs and the dresser -- leaned at various angles. A young and eager-looking Ecuadoran named Franklin carried my bags in and made a fire for me in the fireplace. After borrowing a telephone (the only one in the place, it seemed) to call Satomi I sat in a rocking chair in front of the fire, warming my feet and drinking tea (also made for me by Franklin), wondering at the fact that I was actually there in Ecuador with over a week of "down time" ahead of me. With the fire still crackling I turned off the light and went to bed. Saturday, January 19 I woke at 7:45AM. It was quite cold in my room and I dashed into the bathroom, hoping to get a hot shower. I turned on the hot water tap and waited. And waited... It remained cold. I tried the sink and got hot water right away. Odd... but I wanted to keep my optimistic mood so I washed my hair in the sink, took a quick towel-bath and got dressed. On the way to breakfast I suddenly realized my mistake: I had not remembered that "C" stands for "Caliente" (hot) and I had turned on the wrong tap in the shower. (The taps in the sink were unmarked but I happened to turn on the correct tap in that case. Also confusing things was the fact that the Caliente tap in the shower was on the right, and the Frio, or cold tap was on the left.)

Hosteria San Jorge The sun was out, there were birds singing and roosters were crowing. I noticed there were many, many types of plants, in small garden plots and in containers scattered around the buildings. In the dining room I was the only customer. George's wife tried to explain, and I finally understood, that George was on an overnight "insect tour" with two other guests. (Ah, so that's why he didn't pick me up.) I was served a huge and surprisingly good breakfast: scrambled eggs with ham; yogurt; thick fruit juice (made from a fruit called "babaco", it was delicious); toast with warm apple butter; fruit-filled crepes; "cafe con leche" (which is served as a large mug of warm milk and a smaller pitcher of very strong coffee), and chunks of melon and papaya. I was stuffed; not likely I would be going hungry in this place. While I ate breakfast and continued to read my "Che" book, Franklin (now a waiter) fiddled with a cheap stereo at one end of the room. He put in a variety of CDs, listened to a few seconds of each (Andean flute music, then jazz, then a techno disc...) and finally settled on the Red Hot Chili Peppers. "Dream of Californication" played while I finished my meal. My seat was near a window, and I watched a small group of young children play with a pig outside a small adobe building. I'd had a minor headache when I woke up. The Hosteria was at nearly 11,000 feet elevation so this wasn't too surprising. I took an aspirin and drank a lot of water after breakfast. The headache cleared up and I wondered what to do. It occurred to me that being in this place, some miles away from Quito up a rough road, left me little in the way of options. Irina indicated that George would be back sometime after lunch. I said I was interested in taking a walk (this took a while to communicate) and she hooked me up with Luis, a worker at the Hosteria who would show me the way through the local farms. Luis spoke no English at all but he was a good companion for a walk. He pointed out various plants along the way and told me the Quichua and Spanish names for many of them (most of which I immediately forgot). The Hosteria encompasses 80 hectares (nearly 200 acres) of mostly eucalyptus, pine and cypress forest. (None of these trees are native species, and in fact most of Ecuador's original highland forests have been replaced by non-native trees. The pine and cypress were introduced from Europe, and the eucalyptus was introduced from Australia via Colombia.) There were birds everywhere, ranging from small green hummingbirds to larger hawk-like raptors. (I'm not much of a birder, so don't ask me what they were.)

Potato field near the Hosteria We walked through and around cultivated fields, mostly potato, lavender and lupines (called "chochos", according to Luis). We went a few miles up the hill then rested on a bluff that overlooked the valley, with the city of Quito and the airport spread out below us. (I noted that the airplanes taking off used an amazing amount of runway before rotating and getting airborne. What must it be like taking off on very hot days?) Luis told me we were at around 3,700 meters in elevation. I was a little short of breath and my heart was pumping a little faster than usual, but overall I felt quite good. The weather was terrific -- mostly sunny with a few wispy clouds. A light breeze, warm, came from the east, from the direction of Cayambe (5789 meters tall, or 18,993 feet) which was visible across the broad valley. To the southeast we could see part of Cotopaxi peeking out from behind the clouds. Directly to the west of us, up a gradual slope, the dual peaks of Rucu Pichincha and Guagua Pichincha rose steadily, past the cultivated fields and forests and into treeless areas near their ragged summits. (Guagua Pichincha, the closer of the two peaks, last erupted in 1999. The eruption was spectacular -- a huge mushroom cloud and lots of noise -- but the crater collapsed to the west, sparing Quito from any harm.)

Luis, on a hill overlooking Quito After the walk I spent two hours in a small courtyard of the Hosteria, reading my book and watching two small children (who appeared to belong to the cleaning woman) playing nearby. Irina walked by and, on a lark, I asked her about the horses I had seen corralled nearby. She understood my question to mean I wanted to take a horse right now. I responded (in broken Spanish) that I might like to take a short ride at 3:00, which she apparently interpreted to mean I wanted to go on a three-hour ride. She put me on the phone with someone who also spoke almost no English, but she established that I wanted two horses and a guide. Who was I to argue? Within minutes Luis appeared with a bag of snacks. Together we went to the corral, where two horses were saddled and ready to go. Luis and I rode for nearly four hours, up the slopes of Pichincha, through farmyards and past workers' houses. We stopped and ate fresh fruit -- bananas and under-ripe oranges -- and shared a bag of almonds I had in my pack.

On the trail to Pichincha The horses were quite small (possibly direct descendents of the wiry little Spanish horses that Pizzaro and his gang of thugs rode into Quito in the 1500s) but very spunky. After I had re-learned how to ride (in a past life, some 15 years ago, I was a reluctant horse owner) we picked up the pace, at times racing down grassy paths through the hills at a full gallop. Clouds would blow in over the ridges, engulfing us in fog then quickly dissipate, leaving us again under deep blue skies, with the expansive views again in front of us. During the entire ride Luis and I exchanged fewer than ten sentence fragments. Yes, he is from Quito. Yes, he has children (they are apparently the children I'd seen playing with the pig back at the Hosteria). Luis seemed to smile constantly, unless he was examining the horses' bridles (made of frayed nylon rope and old, hand-forged bits of rusted iron). Luis was gentle with the horses, concerned that they were comfortable. He had hands thick with muscles, and fingernails that were permanently stained. He wore a floppy felt hat and a faded Pink Floyd "The Wall" T-shirt.

"The Castle", built by an Italian farmer

Old house/barn near the Hosteria After a few hours of riding my left knee was starting to hurt pretty badly (the left stirrup might have been too short, but more likely I'm just getting old) and I started to get concerned that I would injure myself and ruin my chances of climbing Cotopaxi at the end of the week. But after limping around on it for a while back at the Hosteria the pain went away. By dinnertime it was fine. At 7:00 I wandered over to the dining room. As at breakfast I was the only customer; the room was empty. I still had no idea if there were any other guests at the Hosteria (aside from the rumored butterfly hunters). There was a fire crackling in the fireplace so I warmed myself in front of it, reading my book and drinking Chilean wine (I purchased an entire bottle -- there seemed to be no other option and I figured I had three days to consume it). I was buried in the book when I heard voices -- American voices -- and looked up to see a couple in their mid-thirties coming toward me. Like me they hoped to eat right in front of the fire; it was quite chilly and there was no heat aside from fireplaces anywhere in the complex. They suggested we share a table, I suggested sharing the bottle of wine and we had a fine time comparing stories. Shelly and David were transplanted Canadians now living in Connecticut. There too were in South America for the first time, and had also arrived the day before. As we sat eating our dinners (good food -- especially the soups) we noticed Franklin running past the windows outside. "He runs everywhere," said David. It was true; any time there was something to be done -- a fire lit, a request for a bottle of water, anything -- Franklin could be see sprinting across the grounds to take care of it. He wore black pants, a white shirt and a black vest. His shoes were as shiny as his young face. We were still commenting on Franklin's eager and speedy service when we saw him run back the other way, past the window again. He misjudged the turn, however, slipped on the grass and went sprawling face-first on the ground. "Oh no," said David, "he saw us watching." Clearly embarrassed, Franklin picked himself up and walked the rest of the way to wherever he was going. When I returned to my room there was a nice fire burning (courtesy of Franklin, I supposed) and I sat in a rocking chair in front of it for some time, reading my book and writing my notes. Sunday, January 20 I took my time getting up, getting a shower (a nice, long hot one this time) and getting myself to the dining room. More eggs, more crepes and fruits, more cafe con leche. As I was eating, a tall man came in and introduced himself: finally, the elusive George Cruz. He sat with me and ate and we talked about the Hosteria, the plants I had seen on my walk, and Ecuador in general. I asked him about the eucalyptus trees. George (an amateur biologist -- trained as a veterinarian, he has some background in science and a particular interest in traditional medicinal plants) said they had taken over as the dominant tree species in much of the Andean highlands. "These trees have two faces," he said. "They have good wood for building and for firewood, very useful. But the roots take too much water, and the oils change the PH of the soil so native plants can't grow." While we were talking another man walked in, an American named Kelly who was one of the insect enthusiasts that George had taken for two nights of "hunting". They had gone deep into the forest, searching for large beetles and other creatures by the lights of lanterns. Kelly was an amateur collector who (so he said) takes his collection into schools to teach children about tropical ecosystems. Kelly seemed nice enough, though his hobby seemed a bit peculiar. I told him I have friends in Japan who keep stag beetles as pets and he said, "Well, not to criticize your friends, but the Chinese and the Japanese are part of the problem here. There's one Chinese guy who comes here all the time and pays children to collect everything they can get their hands on. These woods used to be full of beetles, but now you can hardly find them." Kelly may have had a point about collectors depleting endangered species of insects but most -- perhaps all -- of the beetles kept as pets in Japan are bred for the purpose, not collected. And after stopping in Kelly's room to see what he had captured (and killed before placing in special plastic bags and boxes) I began to see his comments about Asian collectors as a bit disingenuous. On his bed were hundreds of specimens: huge beetles, beautifully colored butterflies, spindly-looking grasshoppers, mantis-like creatures, a giant cockroach... I asked him if he needed import permits to take the stuff into the US. He was a little evasive about this ("technically, yes, but...") and I found myself unconvinced that he was any better than the Chinese beetle merchant he had complained about.

Trying to make sense of George's map I told George that I was hoping to take a long hike, alone, up Pichincha. He got out a piece of paper and drew me a map of farm roads and trails to take in order to get to the summit. Running out of room at the top of the paper he had to draw an inset for the last bit, making the map as a whole appear rather cryptic. But it looked straightforward. I changed into light trekking pants and a t-shirt, packed my rainjacket and sweater into my daypack along with some snacks and a bottle of water, consulted George's map and started walking. The map took me in the same general direction and along the same farm roads as the horseback ride the day before. My legs were a little sore from the horseback riding but in general I felt good and maintained a good pace. I reached a wooden gate that was marked on George's map and climbed gingerly over it. We had somehow detoured around this gate the previous day, but I remembered the farm that followed it, with its barking dogs and its field full of workers turning the soil with short shovels, and its small herd of skinny cows. I passed in front of a tiny, ramshackle house. Three toddlers sat in the dirt of the front yard and waved to me as I went past. Some of the workers stopped what they were doing and waved to me, and I waved back. I stopped to rest on a hill overlooking another herd of grazing cattle. There were no trees or shrubs here, and the ground was trampled and eroded from the rain. The soil between the bristly grass was black and powdery, composted dung mixed with volcanic ash. Scattered here and there were spindly shrubs with yellow, compact flowers. The shrubs looked very much like Scotch broom (if so, another foreign import). As I sat munching cashews and sipping water I saw two horses coming down the hill toward me. On the first horse was Franklin, wearing casual clothes and a felt hat. On the second horse was a heavyset man who said "Hello," and asked in a strong German or Swiss accent if I was staying at the Hosteria. He held tightly to the saddle horn as Franklin led him down the hill. At the point on the map where I was to look for a concrete "reservoir" and a fork in the road (very close to where Luis and I had stopped the previous day) I became a bit confused. There was a small reservoir -- more like a watering trough -- down the hill, but George had drawn a gate on the left fork and here there was a gate-like arrangement of barbed wire at a small two-track road leading off to the right instead. I hesitated, then recalled that Luis and I had stopped at what seemed to be a dead-end just around the corner to the left. This must therefore be the fork, I thought, and I crawled under the barbed wire, pulling my pack behind me. The new track -- which was alternately dirt and close-cropped weeds -- rose gently toward the mountain in what seemed to be the right direction. I walked along, looking for the next landmark that George had drawn, a "house with no roof". On his map the distance was quite short, but I walked and walked with no sign of any such structure. After perhaps two miles on this road it began to descend into a valley. I stopped, considering whether to turn around or continue on. If I turned back then one of two things would happen: either I would get back to the fork and determine that I had gone down the wrong road, in which case I would have lost over an hour in an unwanted diversion, or I would get back to the fork, investigate and determine that I had taken the right road in the first place, which would be disappointing to say the least. If, however, I continued on this unknown road there were only two possible outcomes: either it was the right road and I would eventually make sense of George's map and find the path to Pichincha, or it would be the wrong road but I would have an interesting walk, wherever it went. So I kept going; how far I don't know, but when I finally found the ruins of an old house, its walls crumbling, I concluded that George's map was highly conceptual; there was no real attempt at scale. Onward I went, the track becoming more primitive as it rose up the slope of the mountain. Clouds were blowing in, as they had the day before, and the wind was cold and strong. I spotted the next landmark, a geological monitoring station (an outhouse-sized concrete and brick building with a few rusted antennas on top) and turned up the narrow path that led past the station and to the summit of the volcano. The hill was quite steep now, and I trudged slowly up. I could see nothing ahead (the mountain was engulfed by clouds), and the views down into the valleys were obscured as well. I looked at my watch and decided that I'd gone far enough; it was time to get back to the Hosteria. Putting on a sweater (the wind was now coming from my front side) I started back, half-jogging down the path to keep warm.

The long-awaited "house without a roof" It was a pleasant walk back; the sun came out as I passed the large farmhouse that George had labeled "The Castle" on the map. By the time I reached the Hosteria my feet were feeling like they'd had enough of it. George had given no indication of distance on his map but I estimated (from my typical walking speed) that I'd gone 12 to 15 miles. Not bad, really, considering the altitude (the meteorological station was at 4200 meters, or over 13,000 feet).

Door of an old farmhouse I had dinner once again with Shelley and David, who walked into the dining room a few minutes after I had ordered my meal (an excellent chicken dish in wine sauce). Before they arrived I was talking with a young German named Toby who was waiting in the dining room for a ride into town. Toby was in Quito studying Spanish. His English was good (typical; Europeans always seem fluent in at least three languages) and he told me he had been on a nine-hour horseback ride. He was in pain all over -- didn't want to sit down -- and had gone nearly to the top of Pichincha. (It was odd that I never saw him; perhaps there were other ways up the mountain?) Shelley and David had also gone riding, and they described it as an ordeal. First, the always-eager Franklin (who I had seen leading a different guest down) had started their trip without remembering to bring food for lunch. Second, neither Shelley or David had thought to bring warm clothes. And third, neither of them were experienced riders (David hadn't been on a horse at all other than sitting on a pony when he was a child). David (who works at Jesuit hospital in Connecticut) kept repeating "oh man that was rough" over and over again. At one point they had encountered the German (Toby) who was being guided by Luis. For some reason the horse that David was on and the horse that Toby was on had a disagreement that they tried settling by bolting and running. David had no idea how to stop the horse, but fortunately he didn't fall off. This was Shelley and David's last night at the Hosteria; they had tickets to fly to the Amazon basin in the morning and join a boat trip down a jungle river. I didn't ask if they had ever been in a canoe before. After dinner, and after Shelley and David had hobbled off to their room, George came into the dining room and sat with me. We drank beer and George offered to take me into Quito for a city tour in the morning. I agreed, and we sat and talked more about South American history and about Ecuador in particular. George explained that Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia share a common Inca heritage. They have Andean highland traditions, are more conservative and relaxed that other countries in the area, most notably Colombia ("...and what neighbors they are...") George explained that Colombia's history and culture come from the north, from Panama via the Darien Gap. Colombians are more aggressive people, quicker to become angry and more likely to seek revenge for small slights. The eastern and southern parts of South America (Brazil, Paraguay, Uraguay, Argentina and Chile) have a more European culture. In Argentina and Chile in particular there are large populations of Italians, English, German and Jews who have kept their cultures relatively intact, even as they have adopted the Spanish language. George reflected that Ecuador's culture has more in common with Mexico that with other South American cultures. George talked about the Incas, who in the early 1500s (when Pizzaro arrived) were at their weakest point in history. They were split into two factions, the northern Incas (centered in Quito) and the southern Incas (centered in Cuzco). Pizzaro quite accidentally played into the hands of the southern Incas, making the Incas of the north easy to overthrow. The southern Incas initially capitulated to Pizzaro (to this day the Ecuadorans refer to the Peruvians as "chickens") but in the end it was a long and bloody struggle for Pizzaro to complete his destruction of the entire Inca society. Learning from their old enemy's mistakes, the southern Incas resisted the Spaniards far longer than the northern Incas had. George also gave me a brief history of the Hosteria. He had been working on the place for twelve years. It was originally his father's farm, but it had become clear to Jorge and George that growing potatoes was not going to give the family much of a future. Jorge moved for a time to New Jersey (where George was born -- he still holds a US passport) then moved the family back to Quito when George was very young. George attended college in Quito then began planning what would eventually become the Hosteria San Jorge. Of the 80 hectares of land that comprise the Hosteria, many fields are still under cultivation by non-landed farmers (sharecroppers) who pay a percentage of their harvest to Jorge and George. The result of George's twelve years of work (using cheap materials and cheap labor) is a sprawling complex that includes two different guest wings, a large dining room, a swimming pool, outdoor jetted tub, sauna, Turkish bath and extensive gardens. For the most part everything worked (I sampled the sauna and the Turkish bath after my hike) but at the same time everything looks a bit ragged and amateur-built. (It had occurred to me the first night of my stay that there was no easy escape from my room in the case of a fire. The windows were barred and the exterior door to my wing was locked at night, with no way I could see to open the door until Franklin or someone else came with the key. I had an escape plan worked out in the event of a chimney fire or some other emergency; the bathroom had a small window with a wooden grid in lieu of bars. I figured my ice axe would make short work of it.) Monday, January 21 It was another delicious breakfast but I was starting to crave some variety. The music Franklin chose this morning (after again shuffling through a small pile of discs) was a collection of 1980s dance tunes. I sipped my coffee and ate my crepes while listening to the likes of "Ra Ra Rasputin" and "Won't You Take Me To Funky Town".

Entertaining the kids

Entertaining the kids George came back from a trip to the airport (dropping off Shelley and David, presumably) and said he would be ready to leave for Quito with me in "ten minutes". I finished my breakfast, got washed up, played with Luis' kids for an hour (showed them some tricks with a stained, half-flat soccer ball) and watched Luis repair a blown hose is his old Chevy LUV pickup. Finally, at 9:30 George was ready to go. Rather than take the van we climbed into the LUV with its freshly changed radiator hose and bounced down the road toward Quito. ("Funky Town" kept going through my head as we drove.)

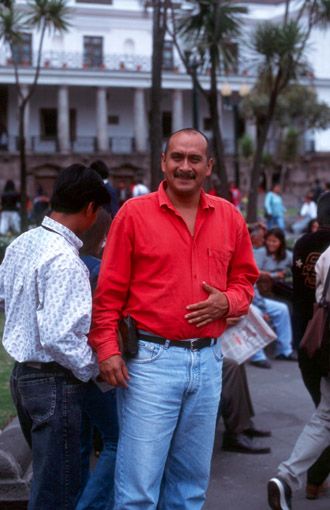

This was my first expedition out of the Hosteria during the day. The road looked quite different in the light of mid-morning than it had at midnight. We passed through a poor, semi-rural district on our way down the mountain. People were sitting idly on the sides of the roads, talking in front of sagging mom-and-pop stores, or stacking old, chipped bricks made of red clay. Most of the buildings were half-finished, giving an appearance of being slowly torn down by time and the shifting earth. Construction methods looked downright scary (by comparison, the sloppy woodwork and leaning walls of the Hosteria looked top-notch). Second and third floors were supported by narrow, hand-poured concrete posts with little in the way of cross-bracing. One moderate earthquake, it seemed to me, and they would all crumple, like so many houses of cards. In Quito we stopped first at George's small office, located in an upper-middle class district of the New City. (Quito has two major parts, the Old City and the New City. The New City is dominated by large, modern office buildings and residential districts, while the Old City -- a United Nations World Heritage site -- contains historic churches, government buildings and more dense, poorer neighborhoods.) I spent an hour on one of George's computers, submitting some homework that was due for an online literature class and checking personal email. George's father and his two sons dropped in at one point, the two boys on mountain bikes and George's father in a Toyota. After the stop at the Hosteria office I asked to stop at the office of Surtrek, the guide service/agency that would be arranging the travel for the next four days. George found the office on Avenida Amazonas, in the heart of "Gringo Town" (more on that later). I paid the balance of my fee for the trek/tour (which was to start the following morning), arranged a time to meet (at the Hosteria at 7:30 AM) and met George on the street outside. It was now around noon, and George drove us through chaotic traffic (colorful busses, rattletrap trucks and dented cars) through two or three tunnels, then finally to the heart of the Old City, where we parked in a public garage that listed its prices at 25 cents per hour, or $19 per month. George was a terrific guide to the city. It was rather like visiting the hometown of a good friend; we swapped stories, personal histories and opinions while wandering through the streets, markets and old churches. George is 40, and his political and social sympathies are not too far from my own. This became most clear when we walked in the most important plaza in Quito, Plaza de la Independencia. I had been quizzing George about Ecuadorian history and politics (a fascinating story of migration, repeated conquest and social upheaval that stretches from pre-Inca times to the modern era, leaving today's Ecuador with little sense of nationhood or shared destiny) when we turned a entered the plaza and found ourselves in the midst of an amazing scene: hundreds, perhaps thousands of indigenous Ecuadorans, wearing their best homespun, children by their sides or in their arms, were massing in the plaza as part of an organized protest and general strike. Battalions of police in riot gear, shields at the ready, lined the sidewalks across from the presidential residence. A paint-splattered armored personnel carrier was parked sideways across one of the main roads, blocking traffic. But there was little tension; the protesters had brought their families (a good sign, thought George), there were bands playing happily, speeches were low-key and the even the police seemed to be having a good time, joking and laughing with each other.

Protest and general strike, Quito

Armored personnel carrier

Riot police at the ready Traditional dancers wearing animal masks (cows and birds) playfully menaced the audience with sticks and whips, making the crowds (George and I among them) scatter to avoid being snapped on the legs. On the front steps of the Cathedral crowds of people held colorful banners and listened to half-hearted speakers.

These people don't look violent...

But maybe these guys do! Rather than being embarrassed about what we had stepped into the middle of, George seemed rather proud. "These people," he said, "They have been pushed down so long and now, finally, they are starting to have a voice. They have the power now to remove presidents." He gestured across the plaza to the white, balconied building with its monstrously large flag. "That's where the president is right now," he said. "No more can the government listen only to the wealthy class, or only to outside interests." These were strong words coming from someone who little to gain, and much to lose, from political upheaval. George's entire livelihood is based on a continued -- or growing -- influx of foreign visitors. George went on to describe how Ecuador's government had been trying during the past decade to emulate Argentina and increase the privatization of most sectors of the economy. The goal of this was a more stable economy with greater foreign investment, but instead inflation had nearly spun out of control, leading to a drastic move: the abandoning of Ecuador's national currency in 2000. "Dollarization" had left vast numbers of people destitute, unable to pay their debts with their now worthless sucres. (The exchange rate in 1999 was something like 8000 sucres to the dollar. A year later the final exchange rate was 25,000 to the dollar.) And meanwhile foreign companies (energy companies, telecommunications companies, etc.) continue to drain money out of the country. (The two major players in the telephone business in Ecuador now are Andinatel and Bell South. I found one Andinetel pay phone in all my walks through town. The others were mostly Bell South, with a scattering of "Porto" cellular payphones making up the rest.) The graffiti around the city was also telling: a frequent slogan was "$=muerte" (death) written in black or read paint. "No privatizar" was another popular theme. Dollarization is slowly stabilizing the economy of Ecuador, but as prices rise to be on par with world norms the cost of living has risen much faster than the average income. There is increased economic activity but this has not resulted in an increase real productivity, and has in fact resulted in a drastically declined standard of living for the average Ecuadoran. This, said George, is what the people are protesting. "It is a kind of revolution happening." Perhaps, I thought, looking at the colorfully dressed peasants and the relatively small number of police. But I imagined it would take a lot more than banner waving and slogans to solve Ecuador's economic problems.

Front steps of the cathedral

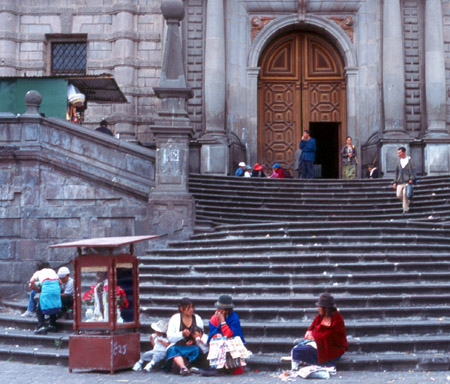

George Cruz Bamano George took me on a walking tour of the many churches in the old city. He explained that the invading Spaniards had emphasized their conquest by tearing down all of the pre-existing Inca temples (and Quito, being the major center of Inca society, had contained many of these temples) and erecting churches directly atop the ruins. There was a Jesuit church, a Franciscan church, a Basilica and others, all of them ornately decorated but most in ill repair. George went on at length about the abuses of the priests in the early years, the thievery and the rapes that changed the complexion of all of Central and South America forever, creating the now-dominant mestizo races. I noticed, however, that George crossed himself as we entered the Church of San Francisco, and in that Church he showed me an enormous and hideous portrayal of hell, filled with tortured sinners, that his mother had made sure he grew to fear as a child.

Beggar at the church door

An inner courtyard, Quito Old City

Franciscan Church, Quito Old City

The Virgin in the box We walked through back streets filled with market stalls and small businesses, and we stopped for lunch (beef, chochos, fried banana and local beer) at an outdoor restaurant near a smaller plaza. When we walked back through the Plaza de la Independencia we found it nearly empty, not a protester to be seen. "Were they told to leave?" I asked. "No," said George, "they probably marched to an open field outside the city." We got the truck from the garage and George began a circuitous trip through the narrow streets, sometimes pointing out notable buildings as we passed. As we neared a major boulevard and turned a corner, however, we saw directly in front of us plumes of black smoke, and orange flames coming from the road. Tires had been scattered, doused with gasoline and set alight. It must have happened just moments before we arrived -- the police were just now showing up, and we slipped past before the traffic had come to a complete standstill.

Riot police, Plaza de la Independencia

The strike turns violent As we pulled away from the scene we noticed that a small Ford in the next lane, also heading away from the riot, was slowing down and had steam emanating from under its hood. Coolant was pouring out onto the street. George looked at the Ford then looked at me, amazed. "Bad day for that guy, eh?" I thought about Luis, who had been under our LUV truck replacing a hose just a few hours earlier. A fine truck, I thought; a fine truck. Before returning to the Hosteria we made a detour to the north to visit the "Center of the Earth" monument on the equator. Not much to see there, other than the large obelisk and globe monument, and a small recreation of a Spanish village. It was a tourist-oriented spot (although I later read that the indigenous history museum that we didn't go into is quite good).

Center of the Earth (equator monument) Driving back, George suggested we stop and have empanadas (deep fried snacks with meat fillings) and cold drinks at a roadside stand. We sat and ate them, smothering them in painfully hot pepper sauce, and talked more about our respective lives. I asked George about the children at the Hosteria, did they all belong to Luis? "Well," said George, "He has five children, but only two are his own." He shook his head and laughed. "Luis is a good man, a hard worker and very kind. Sometimes what happens here is that an older woman, experienced and maybe with children, sees a good man like that..." George made a grabbing motion with his free hand, "I feel a little sorry for Luis." I tell George I know two guys who had similar things happen to them. One I've lost touch with since he married, but the other I have kept track of sporadically. The last time I saw him was two or three years ago, sometime after his marriage (at age 23 to a 38-year old mother of a teenage girl) had fallen apart. I told the story to George and he kept laughing about it, an hour or more after we had left the empenada place ("In America also? Same everywhere!"). but while we laughed I also reminded him that it works both ways; after all, how many young women have found themselves in relationships with older, divorced fathers? I had been confused about George's full name and I finally ask him to explain. In his email correspondence he had always been "George", but on his paintings (six of which decorated my room at the Hostera) he was "Luis CruzB", and on at least one document at his office he was "G. L. Cruz Bamano". It turns out that his father's family name is Cruz, and the family name of his wife is Bamano. He has the American name of George (given at birth) but in Ecuador his first name is legally Luis. Ecuadorans take the name of both families at marriage, leaving him George Luis Cruz Bamano. Back at the Hosteria I ate dinner alone and reflected on what I'd learned about the country so far. I came to the place knowing very little: I knew there were big mountains, some of the active volcanoes, and I knew more or less where it was, straddling the Andes between Peru and Colombia. I knew (in an abstract way) that it was a poor country. But Ecuador, almost unique in South America, never seemed to appear on the radar of the American media. Colombia, of course, was often in the news -- drug warlords, corrupt police and army, kidnappings and street crime -- and Peru, with its Shining Path guerillas, was in the headlines for a decade or more. But Ecuador -- and Bolivia too -- what do we ever hear of these places? Ecuador was, it seemed to me, one of the few places in the Americas that I could not honestly recall reading anything about, save for the occasional mention in a larger travel narrative. Even the book I just finished reading, which describes a 10,000 mile journey through the continent, somehow manages to avoid Ecuador entirely. It had taken me three days to realize that the paintings in my room (two of which were really quite good) were done by George, and to connect that to his request to borrow my camera in the Plaza de la Independencia ("So many faces here, I'd like to paint them..."). But George himself is a set of contradictions, and in many ways he represents Ecuador. His is a tall mestizo who is mostly European yet retains strong pride in his Inca heritage. He well understands the abuses of the sixteenth-century conquerors and their polluted Christianity yet he remains devoutly Catholic. He holds two passports. I re-packed my bags and got to bed early, after enjoying another hour in front of the fire. Tuesday, January 22

With Pablo Montalvo on Pasochoa I woke early, had a final Hosteria breakfast and was sitting there, in the dining room, when a tall, pony-tailed man in a baseball cap and sunglasses walked in. It was Pablo Montalvo, my guide from Surtrek. I said goodbye to the staff at the Hosteria and left with Pablo in his Montero. Some explanation is in order: the guided trek I had originally signed up for (the "Condor Trek") had been listed as a four day expedition with pack horses visiting remote villages and the foothills of some local volcanoes. At the last minute, however, I changed my mind (part of the Condor Trek, which is a well-known route, had been washed out recently anyway) and chose to do an acclimatization trek leading up to an attempt on Cotopaxi. I hadn't read the itinerary carefully and was expecting (as in the Condor Trek) to be sleeping in the hills, in a tent. I was surprised (but not necessarily disappointed) to learn that the horses would be replaced by Pablo's Mitsubishi, and that the tent would be a small hostel near Cotopaxi complete with hot water, a fireplace and delicious, freshly prepared meals. All of this, the guide (two guides, actually: Pablo for the first three days, and a high-mountain guide named Edgar for the Cotopaxi attempt), the four nights of accomodations, the meals, the transportation and any equipment I might have forgotten (I brought everything except a climbing harness) were included in the price, which was $400. I kept adding it up in my head, and I couldn't figure out who (if anyone) was making money on this deal. It was off-season, and I was Pablo's only client. (I was also Edgar's only client on Cotopaxi later in the week.) Pablo turned out to be an exceptionally nice guy. Married to an American from Tuscon, he spoke perfect English and we had lots to talk about as we drove south, through Quito and the farming country nearby to our first stop, Pasochoa. The trailhead for Pasochoa was up a winding road surrounded by lush vegetation that was quite unlike the vegetation at the Hosteria San Jorge. It was apparent that there was more rainfall here, and in fact the lichen-encrusted boulders peeking out from dark green shrubbery made it look amazingly like the foothills of the Cascades. Pablo had remarked that each valley in Ecuador had a different microclimate, and that fact was certainly visible here.

Pasochoa We left the truck parked next to a small power generating station and began hiking. I started walking fast, but Pablo chided me, saying, "you're running". He cautioned me to slow down and take it easy, there was no hurry. He was right, of course; this wasn't going to be a long hike (we made the summit in less than three hours) but it was higher than I was accustomed to. At the top of Pasochoa (4200 meters, or 13,980 feet) we sat for a while eating lunch and enjoying the view of Quito to the north. Unfortunately most of the surrounding mountains were hidden by clouds. The sun was also mostly obscured, and it was rather cold. We descended quickly, taking just over an hour to get to the truck. I had a bit of a headache when we reached the truck, and I realized as well that I had a minor sunburn -- those clouds were deceptive. We drove south along a minor road that connected to the Pan American highway, which took us into Cotopaxi province. There, a few kilometers from the highway down a bumpy road, was the Quinta Colorada Hosteria, a fine little hostel favored by climbers. The hostel was an old farmhouse (packed dirt walls and tile roof) that had been purchased and restored by a French couple (now living in Guyana). The interior walls were painted many colors and the furnishings were light colored wood; it was all quite tastefully done and left a warm feeling. There was hot water (if you waited long enough after turning on the tap) and because it was off-season I had an entire section to myself, with three beds to choose from and my own large bathroom.

Hosteria Quinta Colorada (Cotopaxi in the distance) I took a walk before dinner; the afternoon light was nice, and Cotopaxi was showing parts of its glaciers between the moving veils of clouds. I took quite a few pictures. Near the hostel there was a large farm that consisted of dozens of enormous greenhouses. This was a rose farm, a new and highly profitable industry for Ecuador. Pablo had explained to me that these big operations were taking advantaged of near-perfect growing conditions for roses, which since the 1980s had become one of the country's largest agricultural crops (behind bananas, which are grown in the lowlands, and the potatoes grown in the highlands).

Brickyard

Brickyard There were six other guests, all Germans who had traveled together and were planning to start their Cotopaxi climb the following day. We all ate together at the big farmhouse table next to the kitchen (which was also nicely restored, with long tile counters and exposed roof beams). Dinner was potato soup (outstanding, and very filling) with roast chicken and more potatoes, and a mixed salad of tomatoes and sweet onions. There was also a pitcher of cinnamon liquor that was quite good (and quite strong) and Ecuadoran beer. All this was capped off with coffee and a big layer cake for dessert (really roughing it...). I still had something of a headache and was quite tired (not really sure why) so I excused myself and went to bed early. A fire had been prepared in my room but the fireplace was smoky so I had to open the windows to let in fresh air. The smoke made my eyes itch a bit, and the fresh air made me shiver; it was a feeling I rather liked, as it made me want to crawl under the warm blankets. I did so, and fell asleep quickly. I was in bed for almost ten hours. Wednesday, January 23 For Wednesday Surtrek had planned a tougher conditioning hike for me, this one an ascent of Ilinizas Norte, an old twin volcano to the west of the Cotopaxi region, on the opposing side of the valley. We traveled north on the Pan American for a short while, then turned west on a secondary road. As we made the turn onto this road we saw a neatly dressed mestizo woman standing next to the road. She waved an arm as we approached. "Shall we pick her up?" asked Pablo. "Of course," I replied. She climbed into the back seat and as we drove Pablo engaged her in conversation. She was a nurse, and worked in a small clinic located ahead of us in the valley. Pablo asked what the most common health problems were in this area. Arthritis (from manual labor and the cold weather) and gastric problems (from poor diet). We dropped her off in a lethargic, trash-strewn village and continued onward. The route to the Ilinizas trailhead was long, on bad roads and across three small streams (no bridges, we had to splash through them). We were stopped at one point by a man sitting on a parked motorcycle -- a dirt bike -- who made us buy a five dollar permit. Pablo complained to the man for a few minutes ("For what? There are no restrooms, nobody picks up the garbage and the road is a mess... tell your boss!") but he paid the money. (Pablo told me that the official -- a ranger of sorts -- was sympathetic; he complained also that the government didn't even provide him with a shelter, so he had to stand on this awful road with no protection other than his thick jacket.)

Ilinizas trailhead (3900 meters) The Ilinizas climb was arduous; we parked the Montero at 3,900 meters and climbed 1200 meters (to 5128 meters, or over 16,000 feet) up difficult slopes of crumbling scree and ash interspersed with sections of steep, rotten rock. Midway up, after two and a half hours (mostly on trail; the nastier sections were higher up) we stopped at a climbers refuge where some climbers stop for the night. There we found a small group of climbers from Bellevue, Washington, led by Seattle-based guide/instructor Tim Connelly (of the American Alpine Institute). He and Pablo knew each other and talked for a few minutes before Pablo and I left to continue our climb.

Trail to Ilinizas (summit barely visible) It was another three hours of climbing to get from the refuge to the summit. As we neared the top there were parts that required somewhat dicey rock scrambling above steep cliffs, and there were patches of snow in places. It was also windy, and increasingly cold. After one false summit after another I was starting to get discouraged, and I told Pablo I didn't think I could make it all the way by our 2:30 turnaround time. I was dizzy, my legs were tired and my heart was thumping. And my headache was back. We sat for ten minutes in a spot protected from the wind. I ate an energy bar (it tasted awful) and drank a lot of water. In a final scramble up rotten volcanic rocks we made it to the top, to a pile of flat boulders that formed the summit. We didn't stay long, and descended fast enough to waste a half an hour back at the refuge, where Connelly and his clients shared some of their hot chocolate. As we descended to the parking lot from the refuge, I noticed that Pablo was stopping to pick up various scraps of trash -- candy wrappers, bottle tops, etc. -- along the way.

Near the summit of Ilinizas, 5100 meters After a long drive back to the hostel we had a quiet dinner (the Germans were by now up at the refuge on Cotopaxi) and turned in early. I spent some time messing with a computer that was sitting on a desk in the corner of the small hostel office and managed to send an email to Satomi (I couldn't seem to make my calling card work from there, however, so I couldn't figure out how to call home).

Bart? Thursday, January 24 Thursday was a rest day; Pablo and I first drove to a nearby town (Latacunga?) that had two weekly markets in progress. The first market was an animal market, a chaotic event in which poor farmers (Indians) brought their stock to be purchased by mestizo brokers or by other farmers. Pablo pointed out many things that I would have missed had I been there myself. We watched one negotiation between a seller and a buyer that exposed the class hierarchies of Indians and mestizos. The transaction involved four sheep who were being sold by a middle-aged Indian couple. There were dressed in traditional clothes and hats. Their hands were dirty and their clothes were threadbare. Two little children hid behind their mother's skirt. A mestizo in a nylon windbreaker and a baseball cap was examining the sheep, picking them up by grabbing their fleece, weighing them with his hands and turning them rudely upside down in the dirt to examine their bellies. He finished and made a low offer. The farmer, his eyes lowered, shook his head. Rather than engage the Indian in a reasoned debate about the value of the sheep, the mestizo started berating him. Pablo quietly translated some of it, but it was hardly necessary; you could tell by the body language what was going on. "Are you stupid? Take the money, it's a good offer. There's no meat on these animals. Speak to me!"

Animal market: a humorless negotiation The mestizo was addressing the Indian in a degrading manner, choosing to use the lowest form of address possible in Spanish. (Not the polite "usted", or even the more familiar "tu", but a lower form, "vos", than anything I had learned in high school.) Pablo shook his head and said, "See, the Indian can't even look at him; he just has to hold his anger inside." We watched other transactions; sheep, pigs, chickens, horses, guinea pigs... trucks filled with animals rolled out, and Indians with their newly earned dollars began their long walks home. (Pablo, to illustrate a point, asked a few of the sellers to name prices for their animals. In most cases the reply he got was in sucres, not dollars. Even though the old currency had been abandoned, the rural people still calculated in sucre, then converted to dollars -- at 25,000 to one -- when exchanging the actual cash.)

Loading up at the animal market We heard a band playing and found that the local virgin had been given a day out on the town. This is a tradition in Latin America, where the virgin seems to have a greater status -- is a more important religious figure -- than even Jesus himself. In this tradition some benefactor, perhaps a wealthy member of the community, pays for a band, doles out liquor and sponsors a parade through town, with the statue of the virgin Mary as the centerpiece. In the animal market she (in a large plastic case on a stretcher-like platform) was being carried by laughing young men. She was festooned with dollar bills and coins, and the route of her journey, out the church, through the market and down the street through the center of town, was decorated for the occasion, with palm fronds lining the sidewalks. Little boys ran behind, carrying squirt guns and water balloons and dousing people at random. (This activity was related to a different tradition, that of Carnival which was to start officially in just a few weeks.) We see the virgin's benefactor, a somewhat drunk-looking man with a big grin who is carrying a tin cup and a large bottle of booze. He offers everyone a sip from the cup -- I accept and hope that the alcohol in the rotgut whisky is strong enough to kill all the microbes left on the rim by other celebrants.

The Virgin gets a parade

The town's patron doles out the booze

Indian girl At the nearby fruit and vegetable market Pablo showed me some of the exotic fruits of the region. We bought one called "guaba" (not guava, which is quite different). It was an odd fruit, very long and thin and looking rather like an enormous (as long as my arm) green bean. Cracking open the stiff outer shell revealed a dozen or more walnut-sized lumps of white fuzz. These we picked out one-by-one and put in our mouths. The lumps of fuzz (which are sweet, if a little dry in texture) surrounded flat and shiny black seeds that we spat out. I ate about four of the white lumps then decided I'd had enough. We gave what was left to an old woman at another stall. Another fruit I sampled (but didn't catch the name of) was shaped and colored something like a tangerine, but with one pointed end and a hard, leather-like outer shell. Cracking this shell open revealed an inner sac of dozens of small, jelly-like capsules, each of which included a small seed. The taste was good, but it was a bit messy to eat and the crunch of the seeds was rather off-putting (another acquired taste, I suppose).

"Fresh" fish

Tailoring while you wait

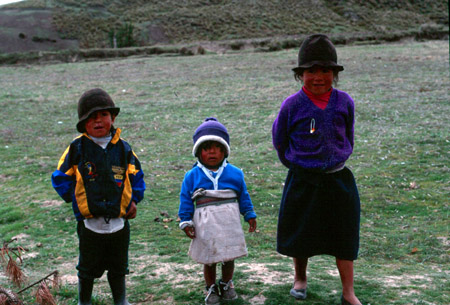

"One Way" We left town, drove up into the hills and around the sides of large valleys toward Quilatoa, our goal for the day. The further we went, the more primitive the dwellings became, until finally we came to a place where nearly all the houses were simple mud huts with heavy thatch roofs. No electricity, no running water or plumbing; this was like something from the middle ages. Indians in colorful clothing beat at the ground with spades, plowing their fields one shovel-full at a time. We looked at the steep cliffs above the valleys and saw cultivated fields -- potatoes -- in impossible locations hundreds of meters up, in small patches of soil between rock outcroppings. We passed more Indians, mostly women with their children, tending animals that were grazing in the weeds along the side of the road. These were people with no grazing land of their own, who traveled for miles each day seeking food and water for their stock.

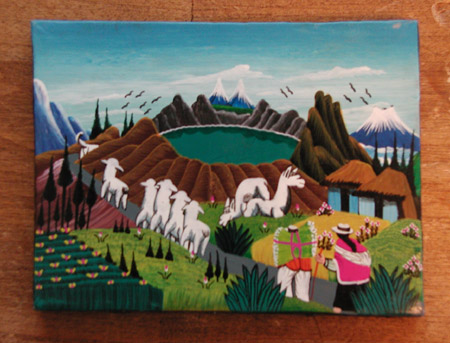

Farming valley near Quilatoa Finally we reached Quilatoa. As we approached the town Pablo told me, "Five years ago there was nothing here, nothing. Just a few small houses." Tourist companies and independent guides started bringing tourists here, however, and guidebooks have recently begun to mention the place. The primary attraction of Quilatoa is its enormous crater filled with volcano-warmed water. What has made the biggest difference for the locals, however, is their art. Since the 1980s, the community has found a market for its unique, colorful paintings. Like Australian aboriginal art these paintings can't be considered traditional (they originated from one man who had an idea to decorate a festival drum, and his style was copied by others) but they do represent one way in which the Indians of this region can express what is important to them (mostly pastoral scenes with animals, farmers and wildlife amid tall mountains) while earning some badly-needed cash. Pablo asked if I wanted to see some paintings. I said, "Sure, why not." He waved an arm and, magically, people appeared with boxes of small paintings that they arranged on the ground around us. Each seller gestured for me to look. Some of the paintings were quite primitive, with little sense of perspective and cartoon-like features. Others were more artistic, more professional. All of the paintings were done on sheepskin that had been stretched across square wooden frames.

Indigenous painting of Quilatoa and the surrounding mountains I bargained with little effort for two paintings. One of them Pablo believed to be particularly good, and I purchased it. The other one I chose because the seller was not being pushy and appeared to me to be in more need of the money, which we quickly determined to be six dollars (she had asked for ten). The woman, like most of the others, sat on the ground in the swirling dust with her face wrapped in the tail end of a shawl. She was probably in her early twenties but may well have had four of five children already. Six dollars would do a lot for her.

Quilatoa crater

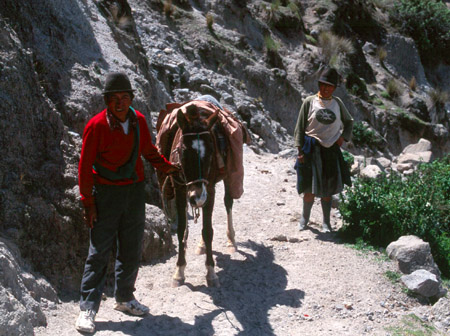

Quilatoa crater It was windy and fine white dust blew everywhere. It was an abrasive, powdery ash that got into every crevice. Two backpackers walked into town, looked briefly at the paintings then continued along the path that circled the crater. I noticed another backpacker lying asleep on the ground in front of a simple hostel, and two more were coming up the road toward the town's entrance. Before departing Quilatoa we walked to the bottom of the crater and dipped our hands in the water. Rather than walk back up, we rode two donkeys back to the rim (another source of cash for the locals). On the way, Pablo engaged his young (perhaps twelve years old) donkey handler in conversation. Pablo tried to teach the young man some useful phrases in English, such as "I have paintings in my house" and learned that this boy, unlike many of his peers, was attending school regularly. Pablo talked to other members of the community before we left. "I try to tell them how to make this place better for visitors. They need to learn how to pick up garbage, to keep it clean. I tell them they should build a community art store and advertise fixed prices. If just two of them worked in the store at a time, then the others could be home taking care of their animals, or taking care of the children, or maybe painting more. But they still don't know how to trust each other."

Quilatoa taxi?

Children, Quilatoa We drove back to the Quita Colorada via the same route, back through the potato fields and the desperate poverty. Pablo talked about the problems of these people, how ignorance, racism and conservative Catholicism combine to keep them a repressed people, in a society dominated by the mestizos. There were agrarian reforms in the 1960s that gave indigenous people title to the lands they had been cultivating for generations, but without the education of experience to know how to make productive use of that land they remain peasant farmers -- farmers with their own class system of the landed and the non-landed Indian.

Mud huts in a valley near Quilatoa In the valley we passed once again through the towns where we had stopped before. As we passed through an area near one of the towns a pair of boys hiding behind a parked truck emerged and launched water balloons at us. One of the balloons entered the driver side window and caught Pablo squarely on the side of the head. Furious, he slammed on the brakes and we skidded to a stop. Pablo burst out of the truck and chased one of the boys, then confronted the boy's mother, who was standing nearby. The two adults yelled at each other for a few minutes, then Pablo stormed back to the truck, clearly unsatisfied with the woman's response. "I told her, educate your children. What if that balloon made me lose control and crash? It almost blinded me. I crash, who pays for that?" He shook his head and snorted, "She just got mad at me, said it was Carnival and what business did I have telling her how to raise her children. She said to me, 'Just because you're a millionaire you think you're better than us.' I'm not a millionaire, she just wanted to ignore the real issue." Pablo's mood didn't stay dark for long. We continued our drive and Pablo dropped me off at the Hosteria, then left to go home, to Quito and to his American wife, who was within two weeks (or possibly just days) of giving birth to their second child. At the Hosteria Quinta Colorada the Germans had returned from their Cotopaxi climb. All had made the summit but they were exhausted, and complained of the strong winds ("You could hear it all night in the refuge, it never stopped," said one of them). I met Edgar, the high-mountain guide who had taken them to the top as a group and would be my guide the next day. We all ate dinner together at the big table in the kitchen, and again I crawled off to bed early, taking just enough time to go through my equipment and prepare my backpack for the climb. For this climb I had brought: plastic mountaineering boots; steel crampons; an ice axe; Gore-tex rain paints and gaters, two pairs of fleece gloves, Gore-tex outer-mits; thick fleece pants and sweater; a rain jacket; two warm hats; a pair of glacier glasses; thick wool socks and long underwear. At the last minute I had also thrown in an expedition-weight goose down parka (in hindsight a very good decision). All of this gear seemed rather silly to be carrying around Ecuador (where temperatures were now heading up toward the 80s) in the week leading up to the Cotopaxi climb, but after hearing from the Germans how cold it was up there I stopped cursing the extra hassle of it all. (I could have borrowed much of the needed gear from Surtrek, but I would be unlikely to get boots that fit properly -- I wear a half-size -- and I had low confidence in the quality of the gear they would provide.) I was in bed for a long time (nine hours) but I didn't sleep very well; I was nervous about the whole thing. The Germans had made it, but they were more experienced. I had made it up Ilinizas (more vertical distance), but it hadn't been easy. Friday, January 25 Friday morning it was cloudy with wind. Cotopaxi was still hidden when Edgar and I loaded our gear into a battered Toyota pickup that had been hired for us. We got in the cab with Raul, our driver, and made our way east, across the Pan-American highway, to a long and winding dirt road that led through small communities and into a forested area. We splashed through two streams and at one of these streams Raul stopped the truck, raised the hood and topped off the radiator.

Raul tops off the radiator Finally we arrived at the parking lot high on the side of the mountain. We could see glimpses of the glaciers as the clouds swirled above us. The wind was blowing hard, and there was rain. We got out of the truck's cab and hurried around to the back, to the protection of the canvas cover that formed a canopy over the truck bed. We put on rain pants, jackets, hats, gloves and our climbing boots and started plodding up the slope (which was composed of ash and scree, difficult to maintain a footing on) toward the refuge, which was visible above us on the mountain near the start of the glaciers. Edgar climbed quickly but I lagged behind, saving my energy. In one hour I was at the refuge. The refuge was large building, yellow in color, with a metal roof. Inside were two kitchen areas, tables for eating, and two large upstairs rooms filled with closely spaced bunk beds. There were climbers coming and going when we arrived. I fell into conversation with two older men from Alaska who had just come from the summit an hour earlier. They looked beat: one of them told me that they had climbed Denali, Aconcagua and Rainier but had never seen conditions like this. "This was harder", he said. "The wind was awful and there was freezing rain. We had ice on everything."

Cotopaxi refuge I decided that if conditions were still that bad at midnight I'd tell Edgar that we shouldn't go. I'd come to Ecuador for fun, not for torture. The refuge was staffed by young Equadorans who joked with each other and practiced climbing holds on the ceiling beams. While arranging my gear (for the tenth time) I met an interesting couple from Germany. They were both in their late twenties and on a grand adventure. First they had hitched a ride on a 40 foot sailboat from Germany to the Caribbean, then made their way to Guatamela where she (Annette, who is on leave from Arthur Anderson in Germany and is fluent in Spanish) had found work for the government. After a short stay there they had traveled south, through Colombia and were now in Ecuador backpacking their way through the country. They thought that perhaps next they would find a boat to crew on (Anton has a degree in mechanical engineering and holds a German captain's license) and head to Australia. At around four in the afternoon the wind calmed somewhat and the sun came out long enough to get a peak at the mountain above us. We couldn't see the summit, of course, but what we could see -- jumbled blocks of ice, fractured glaciers and steep snow chutes -- was impressive.

Looking confident, feeling anything but After a filling dinner (more potato soup, plus beef stew) I climbed into my sleeping bag, hoping to get some sleep before the midnight wake-up. Other started doing the same and by seven the second floor lights were off. I tried to sleep but the staff downstairs (cooks and others) were talking and laughing loudly at the foot of the stairs. This went on for about an hour or so until finally I decided to do something. I put on my boots and my jacket, intending to go outside and use the outhouse. As I passed the group of noisemakers I stopped, point upstairs and said, "Amigos, por favor!" This worked; they moved their party to the other end of the building. Saturday, January 26 Even with the new quiet I was unable to sleep. I had a tightness in my chest that felt like anxiety -- my heart was beating fast and noisily. I suspected it was altitude (the refuge was at 4800 meters, or over 15,700 feet) and this of course made me anxious, worsening the problem. As midnight approached I could hear the wind increasing, building in strength until the metal roof started to make banging noises. I considered staying in bed and just telling Edgar to forget it. But as the others started climbing out of their bunks and putting on their clothes I caught up in the activity as well. After a quick breakfast of yogurt, cereal and hot tea Edgar and I put on our packs and headed up, into the dark and the wind. It was 1:00 AM. Edgar set a reasonable pace, slow and steady, but I asked him to slow down on the steeper parts anyway. The first 200 meters of elevation gain were up a crumbly slope of volcanic rock, scree and ash. The wind was blowing straight down the mountain, gusting erratically to 40 miles per hour or more. I was hard to keep my footing and I was glad when we finally reach the glacier and could put on our crampons. With Edgar leading (we were roped the entire way) we continued our way up into the wind. There was nothing visible in front of us (just the beams of our headlamps casting dim light onto our feet and onto the snow) but if I turned around (which I rarely had an opportunity to do) I could see a few stars in the sky above, and a few constellations of headlamps on the route below. Soon the wind was joined by moisture -- not rain, but a supercooled cloud of mist that froze instantly onto our coats, our pants, and our ice axes. It was horribly uncomfortable. My body seemed warm enough (my feet and hands felt fine) but any time we took a small break -- if I even stopped to take a few extra breaths -- the cold would start to invade through gaps in my jacket. My neck fleece (pulled over my face) was getting a layer of ice on both sides, from the freezing clouds and from my own exhales. For two hours more we climbed in these conditions. The slope was relentlessly steep (it was a narrow ridge, so traversing back and forth wasn't practical) meaning we were sidestepping or duck-walking the entire way. We crossed a few snow bridges and found an area of shelter between two snow-covered rocks. I ate a quick snack, drank some water and responded "sure, fine" when Edgar asked (as he did often) how I was feeling. In fact I felt like crap. We didn't stop for long at the rocks (there was less wind, but still it was terribly cold) and as we made our way up I found it harder and harder to keep going. My head was hurting (as it had for days, it seemed -- I was becoming an aspirin junkie) and I had to take deep, forceful breaths -- sometimes two or three -- which each step. Edgar stopped and waited for me every time I fell back and the rope became taught. Finally I tugged the rope twice for him to stop, tramped up to his position and yelled in his ear, asked him how high we were. "About five thousand four," was his response.

Let's just say it was very dark (Edgar) I took a quick look at my watch; we had been climbing for three and a half hours. Halfway there, and on a good pace for a seven-hour climb (the average). This made me feel a little better, so I signaled him to continue. We made it another 50 meters up before I realized I was deluding myself (dangerously) and called it quits. I was dizzy, I was cold, and even if we somehow made the summit I would still have to get back down, which now seemed highly questionable. Edgar had me lead on the descent, presumably so he could catch me if I fell. It was an agonizing ninety minutes going down. Usually I have less trouble going down hills (less lung work and my knees have always been good) but this was torture. I was stumbling like a drunk and having trouble identifying our route. We paused twice to let other groups pass us (one of these groups eventually turned around, but the other group made the summit) and we made a quick stop in the same sheltered area as before to drink water and eat something (half of a frozen sandwich). By the time we got to the edge of the ice, where we had put on our crampons three or more hours earlier, I was really feeling bad. I was mentally scattered, confused about the direction to go and where to put my feet to avoid falling. I wondered, is this what hypothermia feels like? Edgar called for a stop so he could change the batteries in his headlamp. While he did that I took off my rain jacket -- which was covered in rime ice -- and put on my down parka, which is not waterproof but was a whole lot warmer. (Thank goodness I had brought it; I'd considered leaving it behind in the refuge to save weight.) Edgar got his headlamp working again and we trudged down, through the scree field. At Edgar's suggestion we kept our crampons on all the way to the refuge, which helped keep us from sliding and falling on our butts. Edgar also suggested we short-rope so it would be easier for him to point me in the right direction (and he must have noticed how erratically I was walking). We descended side-by-side, with just a short section of rope between us. Finally we reached the refuge. It was 5:30 AM and still completely dark. There were no lights at the refuge; the generator had been shut down hours ago. In the entry I followed Edgar's example and bashed my pack, my coat and my rain pants against the wall to break up and dislodge the layers of ice. In the dim light of my headlamp I saw that not only was everything soaking wet, everything was also filthy from the red dust of the scree field. I was so exhausted, though, that I couldn't deal with it. I pushed everything into a big pile in the corner of the foyer and went upstairs, collapsing into my sleeping bag. Maybe I slept, probably not; my mind was a jumble as I lay there. Eventually the sun came up. Still feeling horrible, I put on my boots and my down parka, went to the outhouse, then collected my wet things from the floor and brought them upstairs to get them out of the way of the other climbers, all of whom (I had convinced myself) would make it to the top, leaving me the only one to fail. That shouldn't have mattered but it bothered me, and made me feel just that much sicker. But in fact I wasn't the only one to turn back; a little less than half the climbers that day made it to the top. Two of them (also from Washington State) only hiked for fifteen minutes before deciding it was going to be "no fun" and turning back. They were in another room, fast asleep when Edgar and I came back. Another, larger group made it about 100 meters higher than I had before turning back. They had climbed at a slower pace and didn't get back until after sunrise. A small group of very gung-ho looking Americans made it easily, as did the intrepid Anton and Annette. (They, in fact, reached the summit before anyone else. They had no guide, had never been on this mountain before, had old leather boots and offshore sailing outfits in lieu of "proper" attire, but they were young and strong. A bit later in the morning I saw their ice axes propped up against the wall of the entry, both of them coated with a half-inch thick sweater of rime ice.)